| |

WHOO-EEE! Folks, Cookie and me have been parkin’ our wagon in some of the more dangerous areas of Wyomin’ and shootin’ the bull with some of the states more colorful characters, and believe you me we’ve been keepin’ our heads low and our mouths shut! Well at least we’ve been keepin’ our heads low…the mouths shut…well let’s just say we’ve had to push the old wagon to its limits in a quick exit.

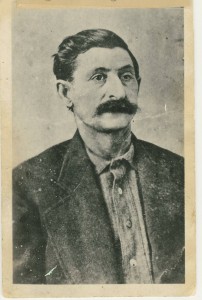

So today we’re jawin’ about a controversial figure in Wyomin’s history. Aren’t most Wyoming figures controversial ya might ask? When ya pick yerself up from someone droppin’ ya for yer smart tongue listen up to the story of Tom Horn!

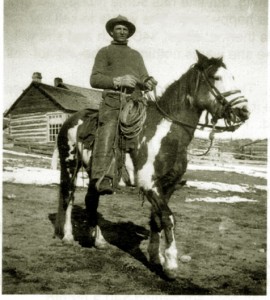

Tom Horn was born in Scotland County, Missouri, in 1860. By his own account, he left home at the age of fourteen. Taking up a series of livestock and stage-driving jobs, he ended up in Arizona Territory. Horn was intelligent and tough. He had an ear for languages and quickly picked up Spanish and later some of the Apache language. He’d also picked up an ability as a tracker.

Therefore, it wasn’t a surprise that while still in his teens he became employed by the Army as a scout and interpreter. The chief of the scouts for the U.S. Army, Al Sieber, recruited Horn in the Army’s campaigns against the Apache. In April 1886, Horn was one of the scouts that escorted the Army column led by Lt. Charles B. Gatewood to find the famed Chiricahua Apache leader, Geronimo.

In his posthumously published autobiography, Horn took credit for the actions of Lt. Gatewood. He claimed it was he whom Geronimo trusted and it was he who convinced Geronimo to surrender. However, the autobiography is the only account of Horn’s involvement with the negotiations.

Whatever the level of his involvement in the surrender of the Chiricahua leader, Horn made a name for himself.The Pinkerton Detective Agency hired Horn, in 1891, to pursue bandits who robbed the Denver and Rio Grande train near Canon City, Colorado. He stayed employed by the Pinkerton’s over the next decade.

About the same time Horn started working for the Pinkerton’s he came to Wyoming. He already had a reputation for certain skills and his services were sought after by some of the prominent ranchers in the area. A few of his “secret” employers included, Ora Haley, John Coble, Coble’s partner Frank Bosler, and the huge Swan Land and Cattle Company.

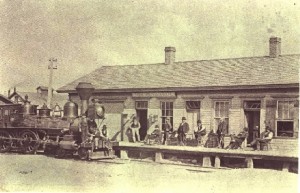

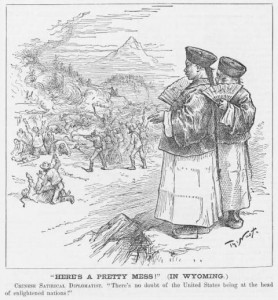

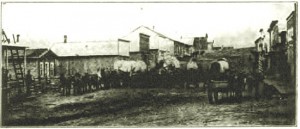

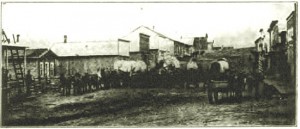

Bosler Depot, 1916 Yep, folks here we are again with those cattle barons. As discussed in the post on the Johnson County War, the large cattle ranchers were suffering from beef glut and blaming the small ranchers for the lack of grazing land and accusing many of rustling. As many ranchers went out of business and many longstanding cowboys and more recent immigrants to the Territory took up homesteads and other land claims, the once powerful Wyoming Stock Growers Association found its membership and its revenues from dues dwindling drastically.

After the public outcry against the Sweetwater lynchings and the backlash of the Johnson County invasion, the large cattlemen decided to take care of the “rustling problem” in secret. Enter Tom Horn.

By May of 1892, Horn was working for the Pinkertons and was deputized by U.S. Marshal Joseph P. Rankin to investigate a murder in the aftermath of the Johnson County invasion. But by 1895, Horn was most likely fully employed by private interests when he was suspected of murdering two settlers.

The first was William Lewis. Lewis was an English immigrant who moved to Wyoming in 1888. He settled southwest of Iron Mountain between the Chugwater Creek and Ricker Creek on the Laramie-Albany County line. Lewis had been jailed for stealing clothing and cheating a boy at a faro game. He was suspected of cattle theft and under a court order to refrain from butchering cattle.

In July 1895, Lewis received a letter telling him to leave the area. He ignored the warning, and on July 31st, as Lewis was loading skinned beef into a wagon he was shot three times. The coroner estimated the shooting had been done from a distance of 300 yards. A rumor circulated about an offer Tom Horn made at the Stockgrowers’ Association and the tall stock detective, Tom Horn, was summoned for questioning.

Horn was located in the Bates Hole region of Natrona County, two counties away. Laramie County Prosecutor, John C. Baird assumed Horn was hiding out after the shooting and prepared an indictment. However, Tom Horn had a number of rancher and cowboy witnesses who were willing to swear straight faced that he had been in Bates Hole the day of the killing. The alibi couldn’t be shaken and the authorities released him.

Horn immediately rode into Cheyenne and indulged in a ten-day drinking spree dropping hints at the truth. “Dead center at three hundred yards, that coroner said!” And he grinned. “Three shots in that fella ‘fore he hit the ground. You reckon there’s two men in this state can shoot like that.” Publicly, he denied everything. Privately, he created a blood-chilling image of himself as a hired assassin.

The second settler was, Fred Powell. Powell homesteaded with his wife Mary and 18 month old son Billy east of Laramie County. The marriage was not a blissful one, and Fred carried a long scar on his face where Mary took a butcher knife to him. Powell was charged with stealing cattle and horses at least seven times, each time he was let go for lack of evidence. Evicted from his homestead he moved to another along Horse Creek, proving up his claim in 1892. Like Lewis, Fred started receiving notes telling him to get out. Powell ignored the warnings.

On the morning of September 10, 1895, Powell and his hired hand Andy Ross were along the creek working when Ross saw Powell clutch his chest and gasp, “My God, I’m shot!” He collapsed and died.

Again, Tom Horn was the first suspect, and was brought in for questioning. Horn shook his head and kept his face expressionless and his voice calm. He had a strongly supported alibi ready, and again he was released.

Enjoying a night of liquor and entertainment provided by the professional ladies of Cheyenne, Horn made vague insinuations admitting to the killings. “Exterminatin’ cow thieves is just a business proposition with me. And I sort of got a corner on the market.”

After a friend once told him that he didn’t think dry-gulchin’ a man seemed very sporting. Horn replied in amazement, “I seen a lot o’ things in my time. I found a trooper once the Apache had spread-eagled on an ant hill, and another time we ran across some teamsters they’d caught, tied upside down on their own wagon wheels over little fires until their brains was exploded right out o’ their skulls. I heard o’ Texas cattlemen wrappin’ a cow thief up in green hides and lettin’ the sun shrink ’em and squeeze him to death. But there ‘s one thing I never seen or heard of, one thing I just don’t think there is, and that’s a sportin’ way o’ killin’ a man.”

After the first two murders, the warning notes were rarely ignored. The lesson learned.

When Fred Powell’s brother-in-law, Charlie Keane, moved into the dead man’s home, the anonymous letter writer took no chances on Charlie taking up where Fred had left off and wasted no time on a first notice: “IF YOU DON’T LEAVE THIS COUNTRY WITHIN 3 DAYS, YOUR LIFE WILL BE TAKEN THE SAME AS POWELL’S WAS.” This was the message found tacked to the cabin door. Keane left, within three days.

For three straight years, Tom Horn patrolled the southern Wyoming pastures. How many men he killed after Lewis and Powell, if he killed Lewis and Powell will never be known.

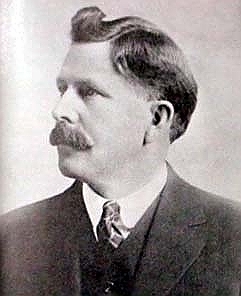

One of Horn’s most notable “clients” was Wyoming Governor W.A. Richards who was being plagued by cattle theft on his own land. Richards was good friends with W.C. “Billy” Irvine president of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association. In a meeting between the two men, Richards told Irvine he would like to meet Tom Horn, but didn’t want him coming to the Governor’s office. Irvine offered to hold the meeting in the WSGA President’s office just down the hall. Horn, in his usual calm manner, informed the Governor he would either drive every rustler out of Big Horn County, or take no pay. But when he finished the job to the governor’s satisfaction he would receive $5000.00. Horn put no limit on the number of men he planned to kill. Though stunned, Richards agreed. After Horn left Richards told Irvine, “So that is Tom Horn! A very different man from what I expected to meet. Why, he is not bad-looking, and is quite intelligent; but a cool devil, ain’t he?”

Horn continued his work as a cattle detective through the 1890s. In 1900, he murdered Matt Rash and Isom Dart, two suspected cattle thieves, in Brown’s Park where the Colorado, Utah and Wyoming borders intersect. The crimes received little notice in Wyoming.

The only thing cattlemen hated more than homesteaders were sheepherders. And while the large and small cattlemen fought amongst themselves the sheepherder entered the territory taking over land and grazing their destructive herds over the already crowded land. But it didn’t take long for the eyes of the cattleman to turn his wrath on the sheepherder. We’ll get into all this in more detail next week, but for now we’re looking at one particular sheepherder Kels Nickell.

Nickell Homestead Seven miles from Iron Mountain was the ranch of Kels Nickell, the only sheepherder in the area. On July 18, 1901, Nickell’s fourteen-year-old son, Willie was shot and killed by two bullets to the back. Willie, tall for his age, wore his father’s coat and hat and rode his father’s favorite horse, and therefore it was believed the killer mistook him for Kels. Though Willie fell face down, someone turned the body over and placed a stone under Willie’s head. There were no footprints or shells left at the scene. Seventeen days after that, Kels was shot, wounding him in the arm, hip and side. While he was in the hospital, masked men clubbed a number of Kels’ sheep to death. The Nickell family moved to Saratoga not long after he recovered.

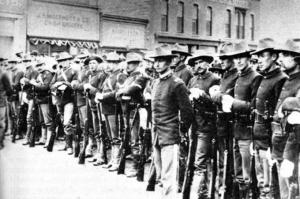

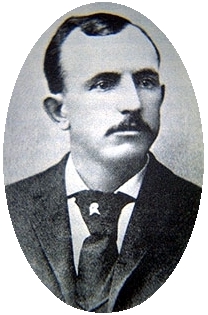

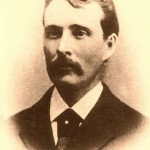

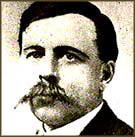

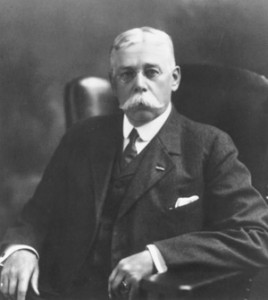

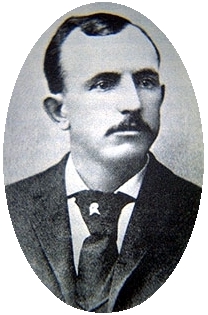

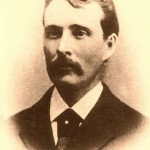

Joe LeFors Deputy U.S. Marshal Joe LeFors was hired by the county commissioners in Cheyenne to investigate the crime. LeFors used letters from a former boss in Miles City, Montana stating the need for someone to do a “secret” job to lure Tom Horn out of hiding.

Horn left John Coble’s place in Bosler meeting LeFors at the U.S. Marshal’s office in Cheyenne on January 11, 1902. LeFors secreted a stenographer, Charles Olnhaus, and a witness, Laramie County Deputy Sheriff Leslie Snow, behind a locked door. Over the course of a two hour interview, LeFors led Horn into making a series of incriminating remarks about the Nickell killing. The most damaging statement being, “It was the best shot I ever mad and the dirtiest trick I ever done.”

Horn allegedly told LeFors that he had been paid in advance and received $2,100 for killing three men and taking five shots at another. He told LeFors the reason there were no footprints is he was barefoot. LeFors asked whether Horn had carried the shells away, to which Horn responded: “You bet your [expletive deleted] life I did.” On Monday, January 13, Laramie County Sheriff Edwin J. Smalley, accompanied by Deputy Sheriff Richard A. Proctor and Cheyenne Chief of Police Sandy McNeil arrested Tom Horn in the bar of the Inter-Ocean Hotel. Deputy United States Marshal Joe LeFors watched.

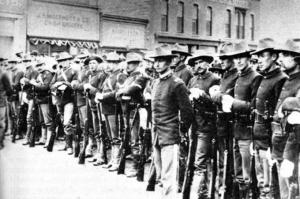

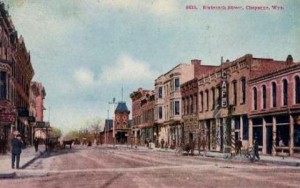

16th Street, Cheyenne, 1902 John Coble paid for Horn’s defense, with the general counsel for the Union Pacific, John W. Lacey representing Horn. The trial was held during an election year with both Prosecutor Walter R. Stoll and Judge Richard Scott up for re-election. On top of this, public interest in the case was overwhelming and the trial received widespread newspaper coverage in Wyoming and Colorado.

Horn’s defense was three-fold:

(1.) Horn was under the influence of liquor, tended to make things up, and became talkative when drunk. Witnesses were produced that Horn had been drinking. He denied making the statements in the Scandinavian. He contended that his jaw had already been broken when he was in the Scandinavian and with the cast he could not talk.

(2.) Horn had an alibi and could not have been in the Nickell ranch at the time of the killing. He was in Laramie City, as proven by the fact that Horn’s horse, Pacer, was lodged at the Elkhorn Livery in Laramie City for a ten-day period at the time of the killing. Witnesses testified that Horn was nowhere near the Nickell Ranch at the time of the slaying.

(3.) The killing could not have occurred as he described to LeFors in the following regards: (a.) Dr. Amos Barber testified, based on learned texts, that the wounds could not have been inflicted with a 30-30 similar to Horn’s. (b.) Frank Stone had bunked with Horn several days later and had observed no injury to Horn’s feet such as would have been produced had Horn gone barefoot. One of Horn’s lawyers testified to having examined the area of the Nickell gate where the killing took place. He testified that the area was strewn with cacti and rocks such that no one could go barefoot in the area. Samples of the rocks were introduced into evidence. (c.) Horn, in his statement to LeFors, described the shooting as coming from one direction. The fatal shot came from another.

Horn took the stand in his own defense. The cross-examination by the prosecutor, Walter Stoll, was devastating. Statement by statement, Horn admitted making the various statements testified to by LeFors, Snow and Ohnhaus with the exception of one statement which Horn did not remember but conceded he might have made.

Horn’s lawyer closed emphasizing all evidence was circumstantial, and Horn’s supposed confession was nothing but drunken boasting.

The prosecution claimed Horn killed Willie Nickell to keep the boy from reporting his presence in the area. But in the day before sequestered juries it is likely they had their minds made up before they entered the courtroom.

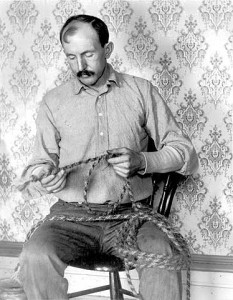

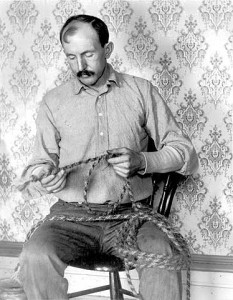

Despite appeals to the Governor to spare Horn and fears that Horns numerous friends would attempt a jail break, on November 20, 1903, Horn was hanged at the Cheyenne jail. Prior to his hanging, Horn spent his time in jail braiding a rope. When it was clear his time was at an end, Horn wrote John Coble: Despite appeals to the Governor to spare Horn and fears that Horns numerous friends would attempt a jail break, on November 20, 1903, Horn was hanged at the Cheyenne jail. Prior to his hanging, Horn spent his time in jail braiding a rope. When it was clear his time was at an end, Horn wrote John Coble:

Dear Johnnie:

Proctor told me that it was all over with me except

the applause part of the game.

You know they can’t hurt a Christian, and as I am

prepared, it is all right.

I throuroughly appreceiate all you have done for me.

No one could have done more. Kindly accept my thanks,

for if ever a man had a true friend, you have proven your-

self one to me.

Remember me kindly to all my friends, if I have any

besides yourself.

Tom Horn remains a controversial character due to the lingering questions regarding his guilt or innocence in the Nickell murder. There’s also a question regarding the WSGA’s involvement with the trial, and the contention Horn was a scapegoat for the powerful cattlemen. Horn’s supporters and later historians questioned his confession to LeFors stating LeFors got Horn drunk and tricked him. Others stand firm that not only did Horn kill Willie Nickell, but an unknown number of men, and that Horn received a fair trial and was represented by one of the finest trial attorneys in Wyoming.

Like the outcome of the Johnson County War, more than the question of Horn’s guilt or innocence is the political shift evident in Wyoming during his trial. Horn, friend of cattle barons was convicted and executed. Their power once unquestionable was on the wane as ordinary Wyoming citizens refused to cower under their heavy hand.

And there it is Cookie a lesson for ya in not shootin’ yer mouth off at the Cheyenne saloon while tossin’ ‘em back and indulgin’ in other…uh…activities! Aw, Cookie, don’t get her feathers all ruffled I know ya don’t frequent the Cheyenne saloons…ya prefer the gals in Sheridan…Cookie come back ya ol’ coot…

Well folks while I go make amends with Cookie, I leave ya to ponder the serious historical developments to the great state of WYO after the Johnson County War and the trial and hangin’ of Tom Horn!

See ya on the trail!

SOURCES:

http://www.wyohistory.org/essays/tom-horn

http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/horn.html

We are back on the trail fresh as spring daisies! “Cookie stop snorin’ and get those biscuits up! Are ya sendin’ smoke signals” Maybe fresh as summer daisies…or late fall daisies…

Anyway we’re continuin’ on down the road of some of the not so bright moments in Wyomin’ history, and ya can’t dig too long ‘fore ya run head long into the Johnson County War. It’s the David versus Goliath of the Wyomin’ Territory and Whooo-eee, it’s a free for all, everyone’s involved, love, hate, murder, why it’s got a little of everythin’ includin’ a trip to the President…Let’s go…

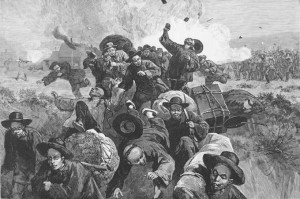

Fifty-two armed men traveled in a private train north from Cheyenne on April 5, 1892. The train stopped just outside Casper, Wyoming, and the men switched to horseback. Their destination was Buffalo, Wyoming, the Johnson County seat. Their mission to hang or shoot 70 men named on a list carried by one of their leaders Frank Canton, former Johnson County Sheriff.

The invaders, as they became known, were comprised of some of the most powerful cattlemen in Wyoming, their top hands, and 23 hired guns from Texas all determined to clean out the “rustlers” plaguing the area. This invasion resulted from long-standing feuds between cattle barons, owning herds numbering in the thousands, and small ranchers running just enough cattle to keep their families fed.

Buffalo, Wyoming circa 1890 The buildup to that night in April 1892, began about ten years prior when Wyoming newspapers outside Johnson County, dubbed Buffalo, “the most lawless town in the country” a “haven for range pirates” who “mercilessly stole” big cattlemen’s “livestock.” Cattle barons cried that they were victims of massive cattle stealing, and Buffalo was a “rogue society in which rustlers controlled everything—politics, courts and juries.”

Contrary to these reports, Buffalo was a town full of ambitious young people working hard to build a community and make a better life for themselves and their families. While far from saints the majority of Johnson County’s citizens bore little resemblance to the ruthless cattle thieves and degenerates as described by the big cattlemen.

During the 1880s, cattle barons in Johnson County and across Wyoming Territory had little concept of the true carrying capacity of the ranges they held as private fiefdoms. These men overstocked the range.

Cattle prices peaked in 1882, bringing more money to the business and more cattle to the range and causing a beef glut. Prices began to fall, yet the cattlemen continued to bring more cattle to the land, weakening the ranges further and driving prices down. A bad drought in 1886 followed by a disastrous winter in 1886-1887 decimated many herds. This combined with the loss of open range, as large ranches fenced in vast amounts of public lands using dubious methods such a “checkerboard control,” strained the already thin tensions between the large and small cattleman.

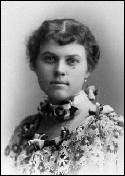

James Averill The large ranchers blamed their losses on the unbridled rustling by small “nesters.” Many of these “nesters” claimed land under the Homstead Act, a piece of law hated by large cattle owners. A small rancher, Jim Averill, who spoke out against the powerful Wyoming Stock Grower’s Association, thought to use the Act to expand his holdings. Averill filed for land under his mistress Ella “Kate” Watson’s name and built her a small cabin giving her a few head of cattle. After five years Kate could claim the title to the land and then according to Jim they would marry and combine their holdings.

Averill received threats from the large ranchers, but ignored them continuing to ranch andrun a store on his own land. Reports were circulated that Kate, a former prostitute, was still servicing men in the cabin Averill built her. Only this time she was paid in stolen cattle earning her the moniker, Cattle Kate. The allegations of prostitution against Kate have been brought into question by historians in current years, as many of the articles claiming this were written by papers owned by association members.

Ella Watson Averill continued to speak against the large rancher even as his own operation continued to grow. The cattle barons, incensed at his rhetoric and the fact he was actually making something of his ranch, continued to threaten Averill and publish articles about the couple’s rustling ring, and Kate’s “side business.” Until on July 20, 1889, led by cattle king Albert J. Bothwell, a gang of vigilantes from the association hanged the couple as cattle thieves.

One of Kate’s ranch hands, Gene Crowder, followed the men to the canyon and witnessed the lynching. He reported what he saw to the sheriff and warrants were issued. News of the hangings spread quickly throughout the west. Newspaper readers were outraged at a woman being hanged. The Salt Lake Tribune commented, “The men of Wyoming will not be proud of the fact that a woman, albeit unsexed and totally depraved, has been hanged within their territory. That is the poorest use that a woman can be put to.”

The Cheyenne Daily Leader had a different take on the lynching. “Let justice be done. All resorts to lynch law are deplorable in a country governed by laws, but when the law shows itself powerless and inactive, when justice is lame and halting, when there is failure to convict on down-right proofs, it is not in the nature of enterprising western men to sit idly by and have their cattle stolen from under their very noses.”

Two days after Jim and Kate were hanged, their bodies were cut down. Six association members, including Albert Bothwell, were brought to trial. But Rawlins authorities were bought off, and no one could be found to testify. Therefore, the men were discharged.

In addition to Averill and Watson, Tom Waggoner, an alleged horse thief, was hanged and his body left for the maggots in 1891. It was contended that Waggoner had amassed a fortune of $30,000 to $70,000 from stolen horse. This despite the fact Waggoner resided with his wife in a two-room sparsely furnished cabin, and one of the two rooms was an attached stable.

Others tried to tie Waggoner to alleged cattle rustling from the Elias Whitecomb’s Standard Cattle Co. Tom Waggoner loaned “Jimmy the Butcher” money to establish his butchering business. Waggoner posted Jimmy’s bond when Jimmy was arrested for rustling Standard Cattle Company cattle. Jimmy also ended up dead. He was buried beside a house belonging to a “cattle detective” working for the Standard Cattle Company.

Efforts were made to control small ranchers from branding their own mavericks or strays. Cowboys suspected of branding mavericks were blacklisted and precluded from finding employment with any member of the Wyoming Stock Grower’s Association (WSGA). Small ranchers found it difficult to participate in roundups. For example, in the 1883 Powder River roundup some 27 wagons (name for a roundup crew) participated, by 1887 only four participated with smaller ranchers being eliminated.

Keeping the small ranchers from the roundups backfired, however. They simply organized their own earlier roundups and could brand and claim all mavericks on the range.

After the murder of Newcastle rancher, Tom Waggoner, the WSGA decided to follow it up with an attack on the small ranchers of Johnson County, namely one, Nate Champion. Champion was a small man with a reputation as a formidable fighter. He ran a herd of about 200 cattle on one of the forks of the Powder River. His cattle grazed on public land, just like the cattle of the big ranchers, and he insisted his animals had just as much right to the grass there as any cattle baron’s herd.

Legally, Champion was absolutely correct, but the big cattlemen did not accept this, and declared him “king of the cattle thieves,” even though no charges had ever been brought against him.

Nate Champion courtesy of Jim Gatchell Memorial Musem The first attempt against Champion was on November 1, 1891. Vigilantes burst into a cabin occupied by Champion and Ross Gilbertson. The cabin was a tiny structure located in Hole-in-the-Wall country about 15 miles southwest of present day Kaycee, Wyoming. Only two men of the five-man squad could squeeze into the cabin holding pistols on Champion.

Champion and Gilbertson were able to get the drop on the men when Champion “stretched and yawned while reaching under a pillow for his own revolver and the shooting started.” It was amazing Champion survived as the shots fired at him were fired at point blank range. In the process, Champion shot one would be killer in the arm and another in the belly. As the intruders fled, Champion recognized one.

Two of the men admitted everything to Powder River ranchers, John A. Tisdale and Orley “Ranger” Jones. With Tisdale and Jones’ accounts and Champion’s identification, Joe Elliott, a stock detective of the WSGA, was arrested. However , by December 1891, both Tisdale and Jones were murdered, but with Champion’s testimony it still looked likely Elliot would be convicted.

In March 1892, the big cattlemen resolved to invade Johnson County and only one month later they boarded a train headed for the southern tip of that county. There they received word that “rustlers” including Champion, were holed up in a cabin at the KC Ranch just a few miles north.

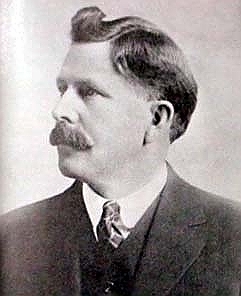

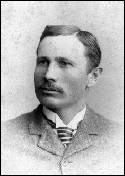

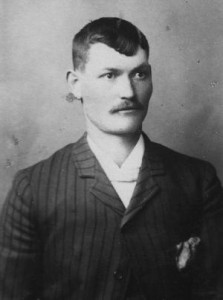

Frank Canton Frank Canton was unrelenting in his opposition to rustlers. After he left office as sheriff of Johnson County, he took a position as a stock detective with the WSGA, and he was known as a merciless, congenital, emotionless killer.

The train that left Cheyenne had a flatcar bearing three Studebaker freight wagons laden with dynamite and other supplies. Various stockmen including W.C. Irvine and Bob Tisdale along with two newspaper reporters, Ed Towse of the Cheyenne Sun and Sam T. Clover of Chicago Herald also traveled north. Once the stockmen and the Texans separated the train continued north under the command of Major Frank Wolcott.

Frank Wolcott Wolcott managed the Scottish-owned V R on Deer Creek. Wolcott came West when President Grant appointed him as a United States Marshal, where he also served as warden of the territorial prison in Laramie. Grant fired Wolcott after the President was inundated with complaints that Wolcott was obnoxious, hateful, overbearing, abusive, insolent and dishonest. His private life obviously wasn’t much better, as he was reported to be “corrupt and disgraceful.”

The special train, under Wolcott’s command, made only one stop to confirm the telegraph line to Buffalo was down. Wolcott did not last long as leader of the vigilantes. He got into an argument with Canton and Tom Smith (a gunfighter from Texas), which led to him resigning his command. Smith became the leader of the Texans and Canton commanded the expedition. They disembarked from the train at Casper only to have difficulties traveling, first due to mud and then a snowstorm. One of the Studebakers broke through a bridge. When they arrived at their first destination, Canton urged attacking at once. The snow grew worse and it took six hours to make it the KC.

There were four occupants at the KC ranch: Nate Champion, Nick Ray (an unemployed Missouri cowboy working the line) and two trappers, Ben Jones, and Bill Walker (who had sought shelter from the storm). In the predawn hours of April 9, 1892, the invaders occupied the stable, a creek bed and ravine near the cabin. Jones came out of the cabin to get water and was captured by the invaders. His partner, Walker, came out next and was also taken. Ray emerged to get firewood and was shot. Champion grabbed Ray and pulled him back into the cabin. During the day the “regulators” and Champion exchanged shots, while Champion kept a log in an old notebook during any lulls.

Me and Nick was getting breakfast when the attack took place. Two men was with us- Bill Jones and another man. The old man went after water and did not come back. His friend went to see what was the matter and he did not come back. Nick started out and I told him to look out, that I thought there was someone at the stable and would not let them come back.

Nick is shot but not dead yet. He is awful sick. I must go and wait on him.

It is now about two hours since the first shot. Nick is still alive.

Boys, there is bullets coming like hail. They are shooting from the stable and river and back of the house.

Them fellows is in such shape I can’t get at them. They are shooting from the stable and river and back of the house. Nick is dead, he died about 9 o’clock. I see a smoke down at the stable. I think they have fired it. I don’t think they intend to let me get away this time.

Boys, I feel pretty lonesome just now, I wish there was someone here with me so we could watch all sides at once.

Champion fought 50 men for hours, wounding three. In the middle of the afternoon, the invaders torched the cabin. Champion emerged from the smoke and was shot down. There were more than 24 bullets in Champion, and the invaders left his body to rot and be eaten by coyotes. Nothing was left of Nick Ray but “his skull and part of the shoulders.”

The invaders, back under the command of Wolcott, took refuge at a friendly ranch, the TA Ranch. The TA was already situated for defense. The house had a seven foot fence around it and was situated in a bend in Crazy Woman Creek. Behind the house was an ice house, perfect as a defensive outpost.

TA Ranch courtesy of Jim Gatchell Memorial Musem Men from around the area rushed to confront the invaders and surrounded the T.A. This posse grew to more than 400 men, and conducted a formal siege led by the Civil War veterans among them.

“Go-Devil” courtesy of Jim Gatchell Memorial Museum For over three days the posse closed in on the “regulators.” On the third day, members of the posse moved toward the TA Ranch house, using a movable fort called a “go-devil” or “ark of safety” made of logs and the running gears of two wagons. The plan was to get close to the house and then use dynamite to force the “regulators” out.

The posse never got a chance to use their new weapon. At the last minute, soldiers from nearby Fort McKinney rode onto the scene and took the invaders into custody. Later, it was revealed, that Governor Amos Barber, a friend to the big cattleman and members of WSGA, summoned the soldiers to save his friends.

Barber telegraphed President Benjamin Harrison, but when his telegram didn’t go through, Barber asked the two senators from Wyoming, Joseph Carey and Francis E. Warren to go to the White House. The senators acted upon the request, and convinced Harrison there was an insurrection.

Once the invaders were taken into custody, Barber assumed control over them and wouldn’t let them be questioned. His interference completely frustrated the investigation and prosecution of the invaders by Johnson County.

While the cattle barons involved escaped justice, the system could not protect them from Wyoming voters.

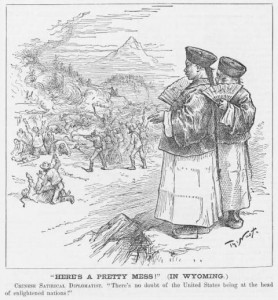

Many Wyoming people were offended by the spectacle of the senators’ late night personal visit to President Harrison to rescue the invaders. The invaders and their supporters continued their attempts to suppress Johnson County and its advocates. This included a fervent attempt to have martial law declared in the state. President Harrison, however, apparently made cautious when great numbers of Wyoming people protested his earlier actions, refused to do that.

The 1892 election was a landslide in favor of the Wyoming Democratic Party, a dig at the predominately Republican WSGA. A Democrat was elected governor and another was elected to the U.S. Congress. At the time, U.S. senators were still elected by state legislatures; enough Democrats were elected to the Wyoming state legislature that no Republican could be selected for the U.S. Senate. Senator Francis E. Warren lost his seat.

The Democrats didn’t retain control for long, as in 1894, following the nationwide Panic of 1893, Wyoming voters threw out the Democrats, the party in power during that economic catastrophe. Francis E. Warren was returned to the U.S. Senate in 1895 and served there for the next 34 years.

Despite mixed electoral results, there were permanent and positive changes in response to the Johnson County War. “Wyoming people had made it abundantly clear—by their votes and by strong resolutions to public officials reported in newspapers– that they would not tolerate abuses like the invasion of Johnson County.”

Perhaps most significantly, the organization primarily responsible for the Johnson County War, the Wyoming Stock Growers Association, was changed forever. Plagued by continuing economic woes, the cattle barons in the association permanently altered this organization in 1893 when they opened their group to all the stock growers in Wyoming.

In what was a galling but necessary action, the small cattlemen of Wyoming, vilified just a year before, were invited to join. This action abruptly halted the overwhelming hostility of the big cattlemen toward the smaller operators and stopped such programs as the confiscation, at point of sale, of suspected rustlers’ cattle by the Wyoming Livestock Commission.

After 1893, a measure of peace descended upon the Wyoming range, although it wasn’t until 16 years later that vigilantism was finally stopped in Wyoming…but we’ll get into that later. 😉

Cookie we DO NOT need a “go-devil”, I don’t care how much ya want one! Daggnabbit, ya show a man a new toy and suddenly the cook thinks he needs a weapon to besiege somethin’…although that is a pretty fancy piece of weaponry…maybe…Okay ya ol’ coot go see iffin’ ya can fashion us one of those…

Oh sorry, folks! While Cookie and me see what we can find to put together our own little siege weapon here, come on ‘round the campfire and help yerself to a cup of Arbuckle’s and tell us what ya think of this brouhaha in Wyoming!

Sources:

http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/johnson.html

Jim Gatchell Memorial Museum, Buffalo, Wyoming

http://www.wyohistory.org/essays/johnson-county-war

http://www.legendsofamerica.com/we-outlawlist-a.html

Chartier, JoAnn and Chris Enss.Love Untamed: Romances of the Old West. The Globe Pequot Press: Guilford, CT, 2002.

Celebratin’ the Cowboy!! Yeee-haw and sign me up!

A big ol’ HOWDY to all stoppin’ by the campfire on the Western Roundup Giveaway Hop, whether you’ve been followin’ Cookie and me for a time, or you’re new to the trail! (Just so ya know Cookie is my trail cook, ramrod, trail guide, and all around pain in my backside)!

I hope after readin’ this blog y’all will make yourself to home and gander about the whole site and past gatherins’ round the campfire.

At the end of the hop, I’ll be tossin’ the names of those who left comments in the Stetson and givin’ away ONE e-book (Kindle or Nook) copy of any of the books featured ‘round the campfire to TWO lucky commenters! So make sure to comment, and Cookie will get yer name in the hat! This is for books mentioned during the hop and also those featured on past Wednesday Western Roundups!!

Now let’s get hoppin’!

What’s romantic about the cowboy? Ya might ask (iffin’ you’ve been under a rock for a hundred or so years). What’s not romantic about the cowboy? Cowboys have been icons of hard work, hard play, and hard lovin’ since they shot onto the American landscape in the 19th Century.

To kick off the blog hop celebratin’ the Cowboy and American West, I’m bringin’ ya a bit of the softer side of these gunslingin’, chap wearin’ heroes!

Below are just a samplin’ of songs, poems and letters showin’ the heart of the Cowboy, and just one of the many reasons we Western Romance writers fell in love with this particular breed of man!

If there’s one thing a cowboy knew it was loneliness on the trail, and the fear another might win his lady’s heart while he was gone for months on a cattle drive. Some put their fears into lyrics, or wrote them in letters home. If there’s one thing a cowboy knew it was loneliness on the trail, and the fear another might win his lady’s heart while he was gone for months on a cattle drive. Some put their fears into lyrics, or wrote them in letters home.

LONELINESS

At nights I think of her a heap,

These quiet nights when shadows creep

Down thro’ the sage, and ev’ry tree

Looks like a black hearse plume to me.

Oh, lonely land and lonely heart,

It surely seems when I ‘m apart

From her I hain’t the least excuse

Fer livin’, and I sees no use

In even daylight comin’, fer

It’s always nighttime without her.

@Robert V. Carr, 1912

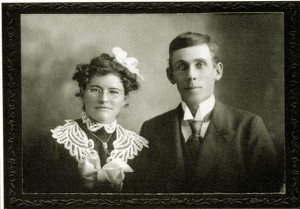

Mittie and Fred Fred Tucker and George Oathanile Bacus both vied for Mittie Richardson’s attention. In 1902, Mittie was sent east to Boston apparently to resolve the situation. In correspondence from family members, it appears that Mittie’s mother did not approve of either George or Fred. Mittie’s mother referred to George as “Backhouse.” In one letter, Mittie’s mother wrote, “I sat there and looked at Fred while he was eating dinner and I though of the old saying that love would go where it is sent if it went into a dogs – – – and I just thought if anybody fell in love with that thing they aught to have him why he can’t even talk I was pleasant to him but O dear.” Both Fred and George wrote Mittie while she was in Boston, each expressing their love. After Mittie’s return, in June 1903 things boiled over in the bunk house with Bacus shooting Fred (Fred survived but fled Wyoming). Bacus sent Mittie a letter of explanation (excuse George’s spelling and grammar):

George Bacus Casper Wyo

June 14, 1903

Miss Mittie Richardson

My Loved One, I sit down to drop you a few lines to let you know that I am on deck yet. I will be back soon to see my littel love again and se what they do weath me for what I have don. I see now where I was foolish for leaven Elmer [LaPash, Mittie’s brother-in-law] toald me to give up and I am sorry I didnt. I took the horse exptoan [expecting] to go to town if I could of seen you before I left, I would not have left there. Now Darling, pleas donant let eny one out side of your folks see this letter I toald ProSiak that I was to blame for shooting and would not give up, but I gess I well now doant tell Fred I am coming back I donant want any more trubele weath anyone. Darling I would like to have a talk weath you. I was not to blame for what happened in the bunk house but had not [illegible] of shot atall but I was excited then and could not help it Well Dear this is cloast to your birth day and I will send you all I can from here that is thre of the pretest fours I can fiend I must close the tears will not lit me rite eny more best washes to you as ever your Love

G O Bacus

…These air sweet for get me nots [forget me nots] it is all I have and hoap they will be recped weath pleasher Hope to see you soon and Mittie when I am in Jale in Laramie Will you come and see me I would like to tell you all about every thing but can not rite it as I havent time no neather have I go paper this is all I have I will be back as soon as I can rais money anouff the countey would send for me but I doant want that I will come back weath out thair assistants if they will let me

P S I will be back to hay if thay will let me out in time

Mittie was not loyal to George or Fred and married another man altogether.

Of controversial origin and changing lyrics, a cowboy standard is a song known as the “Cowboy Love Song,” and reflects the sorrow of a cowboy whose sweetheart, unable to withstand the harsh conditions of the West, leaves him. We know this song as…

Red River Valley

From this valley they say you are going.

I will miss your bright eyes and sweet smile.

For they say you are taking the sunshine.

That has brightened our pathway awhile.

Come and sit by my side if you love me.

Do not hasten to bid me adieu.

But remember the Red River Valley

and the cowboy that loves you so true. (Chorus)

From this valley they say you are going.

I will miss your sweet face and your smile.

Just because you are weary and tired,

You are changing your range for awhile.

I’ve been waiting a long time my darling

For the sweet words you never say.

Now at last all my fond hopes have vanished.

For they say you are going away.

O there never could be such a longing

In the heart of a poor cowboy’s breast.

That now dwell in the heart you are breaking.

As I wait in my home in the west.

Do you think of the valley you’re leaving?

O how lonely and drear it will be!

Do you think of the kind heart you’re breaking.

And the pain you are causing to me?

As you go to your home by the ocean,

May you never forget those sweet hours

That we spent in the Red River Valley,

And the love we exchanged mid the flowers.

Many early drovers who came up the Texas Trail were Confederate veterans. During the war one of the most popular songs with southern soldiers was the sad and haunting Lorena about a lost love, and it remained a favorite among cowboys.

Lorena

Words by the Reverend Henry DeL. Webster

Music by Joseph P. Webster

The years creep slowly by, Lorena,

The snow is on the grass again;

The sun’s low down the sky Lorena,

The frost gleams where the flowers have been;

But the heart throbs on as lovely now,

As when the summer days were nigh;

Oh, the sun can never dip so low,

Adown affection’s cloudless sky.

A hundred months have passed, Lorena,

Since last I held your hand in mine,

And felt that pulse beat fast, Lorena,

Though mine beat faster far than thine;

A hundred months — ’twas flow’ry May,

When up the hilly slopes we climbed,

To watch the dying of the day,

And hear the distant church bells chimed.

We loved each other then, Lorena,

More than we ever dared to tell,

And what we might have been, Lorena,

Had but our loving prospered well —

But then, ’tis past, the years are gone,

I’ll not call up their shadowy forms;

I’ll say to them, “Lost years, sleep on,

Sleep on, nor heed life’s pelting storms.”

The story of the past, Lorena,

Alas, I care not to repeat,

The hopes that could not last, Lorena,

They lived, but only lived to cheat;

I would not cause e’en one regret,

To rankle in your bosom now;

For “if we try, we may forget,”

Were words of thine long years ago.

Yes, these were words of thine, Lorena,

They burn within my memory yet;

They touch some tender chords, Lorena,

Which thrill and tremble with regret;

‘Twas not thy woman’s heart that spoke;

Thy heart was always true to me —

A duty, stern and pressing, broke

The tie which linked my soul to thee.

It matters little now, Lorena,

The past — is in eternal past,

Our heads will soon lie down, Lorena,

Life’s tide is ebbing out so fast;

There is a future — Oh, thank God —

Of life this is so small a part,

‘Tis dust to dust beneath the sod,

But there, up there, ’tis heart to heart.

For some, love came hard. As was the case of Wyoming sheep rancher John Love in his pursuit of Ethel Waxham. For four years John sent letters that followed Ethel from Colorado to Wisconsin back to Colorado, until finally in June 1910, Ethel became John’s wife. For more of their story go to: http://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest/program/episodes/eight/psilikeyou.htm

John Love Muskrat, Wyoming

September 12th, 1906

Dear Miss Waxham,

Of course it will cause many a sharp twinge and heartache to have to take “no” for an answer, but I will never blame you for it in the least, and I will never be sorry that I met you. I will be better for having known you. I know the folly of hoping that your “no” is not final, but in spite of that knowledge… I know that I will hope until the day that you are married. Only then I will know that the sentence is irrevocable. Yours Sincerely,

John G. Love

November 12th, 1906

Dear Miss Waxham,

I know that you have not been brought up to cook and labor. I have never been on the lookout for a slave and would not utter a word of censure if you never learned, or if you got ambitious and made a “batch” of biscuits that proved fatal to my favorite dog… I will do my level best to win you and… If I fail, I will still want your friendship just the same. Yours Sincerely,

John G. Love

April 3, 1909

Dear Mr. Love,

There are reasons galore why I should not write so often. I’m a beast to write at all. It makes you — (maybe?) — think that “no” is not “no,” but “perhaps,” or “yes,” or anything else… Good wishes for your busy season

from E.W.

P.S. I like you very much.

October 25th, 1909

Dear Miss Waxham,

There is no use in my fixing up the house anymore, papering, etc., until I know how it should be done, and I won’t know that until you see it and say how it ought to be fixed. If you never see it, I don’t want it fixed, for I won’t live here. We could live very comfortably in the wagon while our house was being fixed up to suit you, if you only would say yes.

John Love

Ethel Waxham Dear Mr. Love,

Suppose that you lost everything that you have and a little more; and suppose that for the best reason in the world I wanted you to ask me to say “yes.” What would you do?

E.

For the lucky cowboys their true loves came without a fight and remained true to the end. These cowboys settled into lifetime partnerships, either building empires (both large and small) of their own, or seeking new adventures wherever the trail took them.

John and Eula Kendrick (John Kendrick was a Wyoming Cowboy, Governor, Senator with Eula his partner in ranching and politics)

Eula Kendrick In 1889, following time at finishing schools in Boulder, Colorado, and Austin, Texas, seventeen-year-old Eula was reintroduced to one of her father’s former employees, a cowboy named John B. Kendrick. She remembered meeting him before: at age seven she had climbed into the lanky cowboy’s lap and announced that when she was old enough, she intended to marry him. In 1891, she did just that.

Following a church wedding in Greeley and a reception at the Wulfjen residence, the newlyweds left immediately for New York on the afternoon train. When their two-month wedding trip through the Eastern U. S. was over, Eula had to face the reality of her new home: a mud-chinked log cabin fifty miles from the nearest town.

It would be several months before Eula would get to live in that cabin, however. Upon their return from the East, Eula went back to her parents’ home while John went to Montana to finish construction. He felt that the rough bachelor digs he’d left behind were not good enough for his cultured bride. It was a lonely time for both John and Eula and letters flew back and forth between them. For a man accustomed to solitude, separation from a loved one was a new thing for John and he expressed his loneliness eloquently and often during this period:

John Kendrick Do you miss your old man? Not one half so much as I miss “the girl I left behind me.” Somehow the feeling of loneliness is inexplainable. Everything lacks interest: the scenes along the road, the different views of the snow peaks of the Big Horns, things that I used to enjoy so much.

By the end of April 1891, the cabin was still not finished. Fed up with living apart, Eula announced to her husband that she was going to Montana, even if she had to sleep on the floor and cook for herself. This response delighted John to no end:

You can never know how many false notions you have driven from my mind in your proposal to come out and do your own cooking, not that I want you to do it, but I did want so much for you to show the spirit of a true little wife and helpmate and the one thing needed to fill my cup of happiness you have supplied.

The OW Ranch in southeastern Montana was Eula’s home for the next eighteen years. Though isolated and far from friends, she had no time to be bored: she cooked, cleaned, ironed, sewed and did all the bookkeeping for the ever-growing Kendrick Cattle Company.

To read more about the Kendricks go to: http://www.kirstenlynnwildwest.com/blog/?p=5

Or http://www.trailend.org/

Frank Butler and Annie Oakley:

Frank Butler, an immigrant from Ireland, developed a shooting act, banking on the growing popularity of marksmanship displays in America in the 1870s. He and his partner would perform as one of up to 18 acts in a variety show, rattling off trick shots for about 20 minutes. Butler often issued a challenge to any local shooting champion. In November 1875, while he was performing in Cincinnati, someone took him up in it. There would be a match nearby, Butler was told, with a prize of $100. He accepted.

The last opponent Butler expected was a five-foot-tall 15-year old named Annie. “I was a beaten man the moment she appeared,” Frank later said, “for I was taken off guard.” His surprise continued when his young challenger scored 25 hits in 25 attempts — Butler missed his last target and with it lost the match. But he recovered quickly enough to give Annie and her family free tickets to his show, and soon he began courting her. Butler was 10 years older, had been married and already fathered two children. He never drank, smoked, or gambled, traits that appealed to Annie’s Quaker mother. The couple was married on August 23, 1876, although Butler would later claim June 20, 1882, as the date. Perhaps Butler was not yet divorced when he first met Annie, or maybe the later date was given because Annie had lopped six years off her actual age in the midst of her rivalry with the younger sharpshooter Lillian Smith. Either way, the marriage was a happy one, lasting for some 50 years.

Frank often included poetry in his letters to Annie.

“Her presence would remind you, Of an angel in the skies, And you bet I love this little girl, With the rain drops in her eyes.”

After they were married Frank Butler continued to tour with his marksman act while Annie returned home to complete her schooling. On May 9, 1881, Frank sent Annie this poem outlining his plans for their future.

Some fine day I’ll settle down

And stop this roving life;

With a cottage in the country

I will claim my little wife.

Then we will be happy and contented,

No quarrels shall arise

And I’ll never leave my little girl

With the rain drops in her eyes.

The famous couple never really did settle down in a cottage in the country, but spent the majority of their years together traveling the world in various wild west shows. The famous couple never really did settle down in a cottage in the country, but spent the majority of their years together traveling the world in various wild west shows.

Whether riding the range, building a ranching empire, or trailing an outlaw the cowboy’s mind often wondered…

To Her

Cut loose a hundred rivers,

Roaring across my trail,

Swift as the lightning quivers,

Loud as a mountain gale.

I build me a boat of slivers;

I weave me a sail of fur,

And ducks may founder and die

But I

Cross that river to her!

Bunch the deserts together,

Hang three suns in the vault;

Scorch the lizards to leather,

Strangle the springs with salt.

I fly with a buzzard feather,

I dig me wells with a spur,

And snakes may famish and fry

But I

Cross that desert to her!

Murder my sleep with revel;

Make me ride through the bogs

Knee to knee with the devil,

Just ahead of the dogs.

I harrow the Bad Lands level,

I teach the tiger to purr,

For saints may wallow and lie

But I

Go clean-hearted to her!

@Badger Clark

Wylie and the Wild West put some music behind “To Her,” and it’s a beautiful song! Take a listen!

TO HER (WYLIE AND THE WILD WEST)

Since we’re at the beginnin’ of the trail, and talkin’ about strong cowboys with soft hearts, I thought it might be fittin’ to feature three of my favorite books by an author who’s turned many a soul to the joys of the Western!

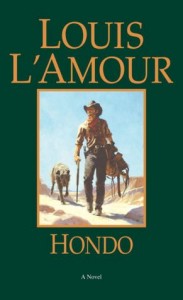

He was etched by the desert’s howling winds, a big, broad-shouldered man who knew the ways of the Apache and the ways of staying alive. She was a woman alone raising a young son on a remote Arizona ranch. And between Hondo Lane and Angie Lowe was the warrior Vittoro, whose people were preparing to rise against the white men. Now the pioneer woman, the gunman, and the Apache warrior are caught in a drama of love, war, and honor.

As far as the eye could see was a vast, empty horizon. Evie Teale had finally accepted that her husband wouldn’t be coming home. Now she and the children were alone in an untamed country where the elements, Indians, and thieves made it far easier to die than to live.

Miles away, another solitary soul battled for survival. Conagher was a lean, dark-eyed drifter who wasn’t about to let a gang of rustlers push him around. While searching the isolated canyons for missing cattle, he found notes tied to tumbleweeds rolling with the wind. The bleak, spare words echoed Conagher’s own whispered prayers for companionship. Who was this mysterious woman on the other side of the wind? For Conagher, staying alive long enough to find her wasn’t going to be easy.

He left the West at the age of seventeen, leaving behind a rootless past and a bloody trail of violence. In the East he became one of the wealthiest financiers in America—and one of the most feared and hated.

Now, suffering from incurable cancer, he has come back to New Mexico to die alone. But when an all-out range war erupts, Flint chooses to help Nancy Kerrigan, a local rancher. A cold-eyed speculator is setting up the land swindle of a lifetime, and Buckdun, a notorious assassin, is there to back his play.

Flint alone can help Nancy save her ranch…with his cash, his connections—and his gun. He still has his legendary will to fight. All he needs is time, and that’s fast running out….

“Cookie! Wipe that sappy grin off yer face!” Ya start talkin’ ‘bout love and the man turns as mushy as his oatmeal!

While I get the stars out of Cookie’s eyes, go ahead and jaw a bit! Why do you love cowboys? What keeps ya buying Westerns or Western Romances? And if ya don’t, why not? Are ya plum loco?

Leave a comment to get yer name in the hat for one of those e-books! And don’t forget this is just day one! Keep stoppin’ in and jawin’ and I’ll keep tossin’ yer name in the hat, the more I hear from ya the better yer chances are! Ya can’t get that guarantee at any faro table in town! (Next chance to comment is Saturday, July 22)

CONTINUE HOPPIN’!!

SOURCES:

http://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest/program/episodes/eight/psilikeyou.htm

http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/cattle.html

http://www.trailend.org/

Chartier, JoAnn and Chris Enss.Love Untamed: Romances of the Old West. The Globe Pequot Press: Guilford, CT, 2002.

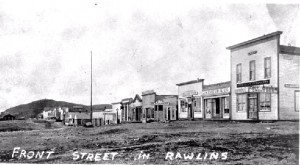

Sweet blazin’ sun, Cookie’s drivin’ this wagon like a runaway stagecoach! He started slappin’ reins and here we are in Rawlins, Wyoming!

Y’all might notice we’re not followin’ a trail for a time as we keep are wagons travelin’ through Wyomin’. For a time we’re gonna look at the bad and the ugly from the Cowboy State’s history, so hang on folks cause this trail is about to get rough!

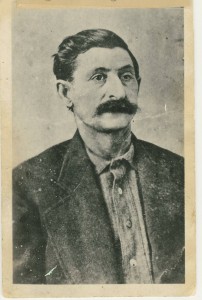

And speakin’ of rough and ugly let me introduce y’all to Big Nose George…

We don’t know much about George Parrot other than he was a cattle rustler, and then joined a gang. Known for his large nose and therefore called Big Nose George, he was a member of a gang of road agents and horse thieves. The leader of the gang was a man named Sim Jan, and they were active in the Powder River country, robbing pay wagons and stagecoaches. Other gang members included: Frank McKinney, Joe Manuse, Jack Campbell, John Wells, Tom Reed, Frank Tole, and “Dutch Charley” Burress. We don’t know much about George Parrot other than he was a cattle rustler, and then joined a gang. Known for his large nose and therefore called Big Nose George, he was a member of a gang of road agents and horse thieves. The leader of the gang was a man named Sim Jan, and they were active in the Powder River country, robbing pay wagons and stagecoaches. Other gang members included: Frank McKinney, Joe Manuse, Jack Campbell, John Wells, Tom Reed, Frank Tole, and “Dutch Charley” Burress.

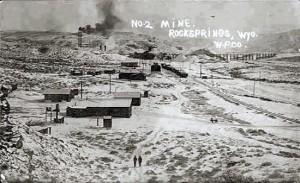

After a series of successful robberies, the gang decided to expand their operation to robbing trains. On August 16, 1878, they planned to rob a Union Pacific train near Medicine Bow by manipulating the tracks so the train would derail. However, as the outlaws waited in the brush for the train, a section crew from the railroad came along and discovered the tampered rail.

Frank McKinney wanted to shoot the rail crew, but Big Nose George and Frank Tole objected, saying they hadn’t come to kill. As the crewmen repaired the track, a railroad foreman rode ahead to stop the approaching train and inform the law that the rail had been tampered with. Forced to abort the robbery, the outlaws watched helplessly as the track was repaired. After the workers left, the gang rode off.

A posse was hastily formed and rode out to apprehend the would-be train robbers. Two lawmen tracked the gang to Rattlesnake Canyon in Elk Mountain. The outlaws shot and killed both lawmen. Wanted now for attempted robbery and the murder of two lawmen, the outlaws went their separate ways.

One of the victims killed that day was Robert Widdowfield. Widdowfield was born in County Durham, England, the son of a miner. In 1870, when Widdowfield was twenty-one, the family moved to America and settled in Wyoming where Robert became a deputy sheriff in Carbon County. On August, 19, 1878, he became Wyoming’s first officer to be killed in the line of duty.

The Union Pacific Railroad doubled their efforts in tracking the gang members and county authorities offered a $10,000 reward for their capture. Frank Tole was killed the next month while attempting to rob the Black Hills Stage line.

“Dutch Charley” was apprehended in 1879. However, when the westbound train transporting the outlaw to Rawlins for trial passed Carbon it was stopped by a mob. “Dutch Charley” was forcibly taken from the train and hanged from a telegraph pole, with one of the widows kicking the barrel out from under “Dutch Charley” and ending his career.

Two years later in Miles City, Montana, Big Nose George, in a drunken stupor, bragged about killing two Wyoming lawmen. A telegraph was sent to Rawlins, and in July, 1880, Sheriff James Rankin of Carbon County went to Montana to collect his prisoner and bring George back to Wyoming. A second time, the train bringing a gang member back was stopped in Carbon by the same mob that lynched “Dutch Charley.” Big Nose was hauled off the train and prepared for hanging. But the outlaw confessed and pleaded for his life, promising to tell all he knew if they let him live. The vigilantes cut him down and he was allowed to continue the journey to Rawlins to stand trial.

When he arrived in Rawlins, he recanted his confession after he was told if he pleaded guilty there would be no trial if his plea was accepted and he would face a mandatory death sentence. His trial began in November of 1880, and he again changed his plea to guilty. The plea was accepted and on December 15, 1880, he was sentenced to hang on April 2, 1881.

While Big Nose was in jail, he stated Frank McKinney claimed to be Frank James, which led to some speculation that Frank McKinney and the gang’s leader, Sim Jan, were Frank and Jesse James. The only gang members ever caught were: Frank Tole, “Dutch Charley,” and Big Nose George. McKinney, Jan and the rest of the gang disappeared.

George attempted to escape on March 22, 1880. Parrot managed to file the rivets of the heavy shackles on his ankles, using a pocket knife and a piece of sandstone. After removing his shackles, he hid until jailor Robert Rankin (brother of Sheriff James Rankin) entered the area. Big Nose struck Robert Rankin with the shackles, fracturing his skull, but Rankin fought back and called out to his wife, Rosa. Rosa grabbed a pistol and forced Big Nose back into his cell.

News of the attempted escape spread through Rawlins, and a mob descended on the jail determined to see Big Nose hang. They dragged Big Nose George from the jail to a telegraph pole on what is now Front Street. A crowd of about 200 people gathered. The first effort using a Kerosine barrel was unsuccessful. On the second attempt, Big Nose was made to ascend a ladder leaning against a telegraph pole. When the ladder was pulled out from under him, Big Nose managed to get his hands free and clung to the pole begging for someone to have mercy and shoot him. No one did. Tired, Big Nose let go and strangled to death.

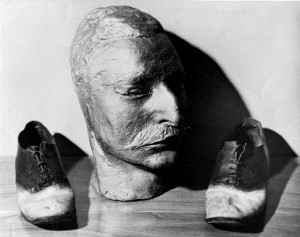

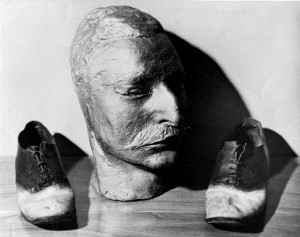

The body was left hanging for hours until the undertaker cut it down. With no family to  claim the body, Doctors Thomas Maghee and John Osborne took possession of it. The doctors wanted to study the outlaw’s brain for the purpose of determining whether there were any visible criminal abnormalities. The skull cap was removed and given to Lillian Heath (later Lillian Nelson), a fifteen-year-old apprentice of Dr. Maghee. Heath, who became the first woman doctor in Wyoming, used the skull cap as an ashtray, pencil holder and doorstop until her death. Though Dr. Maghee acted within the medical ethics of the time, Dr. Osborne’s activities became bizarre. claim the body, Doctors Thomas Maghee and John Osborne took possession of it. The doctors wanted to study the outlaw’s brain for the purpose of determining whether there were any visible criminal abnormalities. The skull cap was removed and given to Lillian Heath (later Lillian Nelson), a fifteen-year-old apprentice of Dr. Maghee. Heath, who became the first woman doctor in Wyoming, used the skull cap as an ashtray, pencil holder and doorstop until her death. Though Dr. Maghee acted within the medical ethics of the time, Dr. Osborne’s activities became bizarre.

Osborne first molded a death mask of George’s face using plaster of paris. The mask was without ears because while George struggled at the end of the rope his ears were torn off.

Next, Osborne removed the skin from the dead man’s thighs and chest, which he shipped to a tannery in Denver with a set of grotesque instructions. The tannery was to use the skin, including the nipples, to make him a pair of shoes and a medicine bag. When Dr. Osborne received the shoes, he was disappointed to find they didn’t include the nipples, but proudly wore them despite his instructions not being followed.

The rest of Big Nose George’s dismembered body was kept in a whiskey barrel filled with a salt solution for about a year as Osborne continued his dissection and experiments. Finally, the whiskey barrel was buried by Osborne’s office in Rawlins.

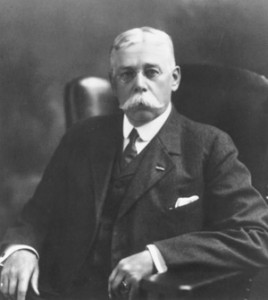

Despite this odd behavior, Osborne was elected as Wyoming’s first Democratic governor, in 1892. Although, the circumstances surrounding his election are a bit sketchy, and it is often said he sneaked into office when the Republicans weren’t looking. Returns from Converse and Fremont Counties were delayed, and the State Canvassing Board was unable to certify the results. Taking matters in his own hands, Osborne took the oath of office on December 2, before a notary public and allegedly crawled along a ledge of the State House and in through the window into the Governor’s Office and refused to leave. The scene culminated with a wrestling match between Acting Governor Barber’s secretary and Osborne for the key to the office.

Governor Osborne wore the shoes made of George’s skin to his inaugural ball, which seems fitting since it appears he was as much a criminal as Big Nose. Governor Osborne wore the shoes made of George’s skin to his inaugural ball, which seems fitting since it appears he was as much a criminal as Big Nose.

Big Nose George was all but forgotten until May 11, 1950, when a construction crew excavating for a new building unearthed a whiskey barrel filled with bones. Included in the mass of bones was a skull with the top sawed off.

A citizen recalled Dr. Lillian Heath Nelson kept a skull cap. Nelson was still alive, but well into her eighties. Her family was contacted and her husband brought the skull cap to the scene, it fit perfectly with the skull found in the barrel. Subsequent DNA testing has occurred and verified the results.

Today if you’ve got a hankerin’, the Carbon County Museum in Rawlins displays Big Nose George’s death mask, his skull and the infamous shoes. Also on display, is a watch given by the County Commissioners to Rosa Rankin for stopping Big Nose’s escape. The shackles used on Big Nose during his hanging and the skull cap are on display at the Union Pacific Museum in Omaha, Nebraska. The medicine bag has never been found.

There ya go, folks! Not a pretty story, and frankly Cookie’s been yarkin’ in a pail since George was skinned and turned inta shoes! Truth be told, I’m lookin’ for my own pail! But if yer lookin’ for somethin’ a little different to see on the trail head on over to Rawlins and take a look at man-shoes!

See ya on the trail! Move over ya ol’ coot, and hand me a bucket!

SOURCES:

http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/rawlinsa.html

http://www.legendsofamerica.com/wy-bignose.html

http://www.carboncountymuseum.org/bignose.html

Whoa Nellie!! Hope y’all are in the mood for more fireworks, cause today Ms. Charlene Sands is joinin’ us ‘round the campfire and she’s brought enough hot cowboys to have y’all seein’ red, white, and blue stars!! Why I had Cookie douse the ol’ fire since the heat from the Worth cowboys was heatin’ up my coffee near to boilin’!!

Keep readin’ after ya pick yerself off the floor, cause Charlene is sharin’ her top ten truths about cowboys! If ya didn’t know why we love these men before, Charlene clears it right up for ya!!

As a special treat Charlene is sharin’ the covers and blurbs for her upcomin’ releases EXQUISITE ACQUISITION and WORTH THE RISK!! So keep yer eyes on the blog ‘til the very end folks, ya don’t wanna miss a cowboy they’re thick as flies ‘round here today!

And Charlene is addin’ a real firecracker of a prize for one commenter, a $15 Amazon gift card!! Whooo-eee and pass Cookie’s sonofagun stew!! Ya could get yerself the whole Worth clan for that!! Just leave a comment and Cookie will get your name in the hat!

Here at the campfire we tend to focus on historical westerns, but I enjoyed this series so much and thought it was a fun idea to include a historical givin’ us a look at where it all began for the Worth family! I had to feature the Worths of Red Ridge!

So let me introduce ya to the Worth cowboys and the women strong enough to rope, tie and brand ‘em…

The passionate, impulsive evening Tagg Worth had spent in the arms of brown-eyed beauty Callie Sullivan was madness. Visions of their tryst still haunted him, but their one-night stand was a mistake the wealthy rancher swore he would not repeat. Hawk Sullivan’s daughter was strictly off-limits—especially since Hawk’s main goal in life was to put Tagg out of business. The passionate, impulsive evening Tagg Worth had spent in the arms of brown-eyed beauty Callie Sullivan was madness. Visions of their tryst still haunted him, but their one-night stand was a mistake the wealthy rancher swore he would not repeat. Hawk Sullivan’s daughter was strictly off-limits—especially since Hawk’s main goal in life was to put Tagg out of business.

Then, suddenly, there was a baby on the way. His baby. Tagg vowed to do the right thing, no matter what it cost him. But his inconvenient new bride tempted his solitary heart down a path a Worth didn’t dare follow….

KIRSTEN’S THOUGHTS: Okay, so I read this series a little out of order and actually read THE COWBOY’S PRIDE first, but after meeting Tagg and Callie in that story I instantly clicked “buy” for CARRYING THE RANCHER’S HEIR. They were such a great couple, and I had to read their story. I’m SO glad I did. Tagg and Callie’s romance is a page turner that’s sure to blister your fingers.

Both Callie and Tagg are people you instantly like, and Charlene does a beautiful job of bringing them and their story to life. Since the premise of the story is laid out in the blurb, I’ll say I was a little worried Callie might be a doormat heroine, letting Tagg walk all over her just to hold onto him. But she is anything but, and I found myself drawn to her character. A smart, resourceful, capable woman who could raise a child without Tagg, but a woman who is tenderhearted and wants to build a life with the man who holds her heart. I appreciated that she didn’t play games, or keep the baby hidden forever, but was open and honest with Tagg throughout their relationship, even when he was holding back.

Get ready to meet a cowboy “worth” sighing over in Tagg. He has his moments when you wonder if he was bucked off too many times as a rodeo star, but his doubts are understandable when he’s marrying the daughter of his family’s fiercest competitor and his first marriage ended in tragedy. Plus, Tagg isn’t a jerk, or is hurtful on purpose. Despite his past heartache and current business issues with Callie’s father, Tagg is determined to make it work with Callie and give their child a home, he just doesn’t realize the harder he “works” at it the more he fails, until he realizes what’s really needed in the relationship is his heart.

This is a couple you’ll really pull for, and will be riveted to their story until the final HEA, as Charlene takes you right into the heart of Red Ridge and the Worth family.

He’d been ready to move on, to marry a woman who’d provide him with heirs. But a year of separation hasn’t slaked rancher Clayton Worth’s raging desire for his soon-to-be ex-wife. And Trish is as unpredictable as ever. Her mysterious reluctance to have kids was what drove them apart. Now Trish is back in Red Ridge, mother to a baby girl. The irony is maddening.

Trish urgently needs to finalize their divorce before Clayton’s irresistible charm can melt her resolve. Because his touch awakens a consuming hunger that hasn’t died. They’d thought it was all over between them…but their hearts have other ideas.

KIRSTEN’S THOUGHTS: I have a confession; I bought this book for the cover! Because…well are you blind, look at that cover. Rugged Cowboy + Baby= Adorable. But that being said once I started reading I was hooked and fully involved with Clay and Trish’s story, and I was hooked on Charlene Sands’ books. Charlene gives us two people we can rally behind and I so wanted these two people together. They just belonged together, and it was obvious the moment they’re on the page together.

Clay Worth is in the sometimes unenviable of being the eldest son. It falls on his shoulders to carry on the Worth legacy, and in typical older brother fashion he often carries more than he has to instead of sharing the load. He’s also a man used to hard work, but always getting what he wants on his terms. But as much as Clay wants to hold onto his resentment being around Trish and little Meggie breaks down his resistance and watching him charm his wife and baby Meggie was a tender journey.

Trish is a woman who’s worked hard for everything and you could feel her need for someone to care enough to work hard for her and her heart. I liked Trish, and sympathized with her desire to have Clay’s understanding about her needing to keep the business she built going, since she’d put her heart into it and at that time it was her baby. But while building her own business and struggling with her own doubts she added to the distance between her and Clay. Through the story Trish learns to trust and to lean on someone else leading her to the truth of what she’s wanted all along.

Both as stubborn as a mule it was sometimes fun and sometimes heartbreaking to see these two slowly let their walls down and find the truth behind all the misunderstandings and hurts of the past. Again Charlene’s characters are so real and she places you so deep in their lives you wish you could call them up and tell them to wake up and smell the burnt toast (because these two have enough passion for each other to burn toast without a toaster), they were made for each other. 🙂

Penny’s Song, founded by Clay and Trish, is a sweet thread that runs through both CARRYING THE RANCHER’S HEIR and THE COWBOY’S PRIDE, as each person adds their own touch to the charity.

![CSandsACowboyWorthClaiming[1]](http://www.kirstenlynnwildwest.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/CSandsACowboyWorthClaiming1-647x1024.jpg)

Cowboy Chance Worth gets more than he bargains for when he saves damsel in distress Lizzie Mitchell. He has come to Red Ridge, Arizona, to rescue her family’s failing ranch and find Lizzie a suitable husband. Too bad it wouldn’t be honorable to keep the little spitfire for himself!

Lizzie may be innocent, but she’s not naive. Fully determined to find her own way in life, she doesn’t welcome Chance’s intrusion. But when he plans to leave she realizes she may not be ready to see the back of him just yet!

KIRSTEN’S THOUGHTS: As much as I loved Clay and Tagg, I was thrilled when I found out Charlene was giving us “the rest of the story” and providing a look into the past and where it all began for the Worths of Red Ridge. In Chance Worth and Lizzie Mitchell, I saw where the Worths inherited not only their land, but their honor, passion, pride, and hard heads, as well as their legends.

It’s been a long time since Chance has known what a real home and family are, but he comes to Red Ridge to honor a debt to the one man who’s been most like a father to him, Edward Mitchell. Chance’s loyalty to Edward and Lizzie, and his teasing nature along with all that cowboy charm makes it easy for this hero to stroll right into your heart.

Elizabeth, “Lizzie,” Mitchell took a little longer to warm up to, but once you saw beneath all the sass to the woman who worked as hard as any man, loved her grandfather with all her heart, and just wanted to be treated like a woman it was easy to appreciate why Chance admired her and fell for this brave woman.

Chance and Lizzie’s romance is filled with tough times on the trail, both literally and figuratively, and sweet moments that warm the heart. Their mutual desire for home and someone to accept them just as they are, and the moment they recognize they found that person in each other will melt your heart. Their romance builds slowly as they learn to trust and rely on the other’s strengths, so by the time they admit their love you fully believe it, because you’ve seen it grow from reluctant partners on the trail to lovers and friends.

One of the most interesting and enjoyable aspects of this series is that the stories revolve around the relationships. There are villains, but their role is minor compared to the couples working through their inner demons and doubts to tough it out and build a lasting relationship. I also liked the Worth family’s legacy of giving to ill children, Penny’s Song in CARRYING THE RANCHER’S HEIR and THE COWBOY’S PRIDE and Sarah Swenson in A COWBOY WORTH CLAIMING is a wonderful link from generation to generation.

These are all brilliant stories and if you’re looking for a great summer read, look no further! But you’ll love them just as much in spring, fall, or winter, too!! Don’t miss out on the Worths of Red Ridge!

Don’t get all jittery like a cat on caffeine there’s still a Worth Cowboy lined up to keep us hotter than an Arizona summer…Jackson Worth’s story, WORTH THE RISK, will be release October 2012!!

What a Cowboy Does What a Cowboy Does

in Vegas…

Cowboy entrepreneur Jackson Worth wakes up next to trouble…literally. His new business partner, boot boutique owner Sammie Gold, should have been off-limits, but something about her sweet vulnerability has gotten under his skin. Working with her is torture, as are the memories of what happened in Vegas….

A one-night stand with the cowboy? What on earth was Sammie thinking?

Jackson Worth is drop-dead gorgeous and completely out of her league. But if

Sammie wants her happily-ever-after, she’ll have to shed her girl-next-door image to seduce the confirmed bachelor once and for all!

Iffin’ you’ve read all about the Worth boys and are just sittin’ there waitin’ for Jackson’s story ride on over and get a copy of EXQUISITE ACQUISITIONS! Go Ahead and start fannin’ now, this book sounds HOT!!

For Macy Tarlington, the only good part of seeing her legendary mother’s possessions sold at auction is ogling Carter McCay, the tall Texan who buys the famous diamond ring. Even better is seeing him again when he rescues her from the paparazzi like a white knight in a Stetson.

Carter whisks her to safety at Wild River Ranch, hiding her identity by day and lusting after her by night. Yes, he’s sworn off love. But with the Hollywood runaway starring in his every fantasy, Carter may find Macy too much temptation—even for a hard-hearted cowboy.

TOP 10 TRUTHS ABOUT COWBOYS BY CHARLENE SANDS

We all have our own interpretation of what a cowboy truly is. In romance novels, we tend to gloss over the reality of what it takes to be a true cowboy. We take our fantasies seriously and dive in, head first and our cowboys have a lot to live up to.

But take it from this greenhorn, who once spent 2 hours in a saddle riding a tall horse named Champion over hills, through tunnels and along pastures of sunny downtown Burbank; the trail is a dust bowl of grit, horses are total fly magnets and without shade, the perspiration rate requires more than a woman’s Secret deodorant. In short, there is nothing really romantic about what cowboys do. Sigh….