Folks, Cookie stopped the wagon at Rock Springs, Wyoming today. Why? As my eye wonders around…that’s what I’d like to know…Why? Just kiddin’ all ya fine citizens of Rock Springs out there, I’m just joshin’ with ya…kinda.

Aw right, Cookie, I’ll stop. Ol’ scudder is afraid he might have to get into a bit of fisticuffs iffin’ I don’t stop. It can get rough down here, and that’s what we’ll be talkin’ about today, when it got real rough and Wyomin’ history took a bit of a turn for the worst.

So while Cookie breathes a sigh of relief that his hide is safe…for now, let me tell y’all a bit about the Rock Springs Massacre!

Since gold was found in California, in 1849, Chinese immigrants started arriving in the West. California welcomed them, at first, a much needed source of labor. Soon Chinese men worked alongside whites from farming to railroads and shops. Even after the transcontinental railroad was finished and thousands of jobs were lost, the Chinese stayed. They didn’t mind living eight or nine to room to save money, and they accepted jobs at lower rates of pay. “Taking jobs away from whites.”

In July 1870, white workers in San Francisco led a large street demonstration making it clear Chinese weren’t wanted, and should consider their lives at risk. In Los Angeles, October 1871, a fight between rival Chinese gangs broke out and whites flooded into the neighborhood murdering 23 Chinese (no one was charged with a crime).

But none of this violence kept the Chinese from coming to the United States. They referred to themselves as Sojourners, meaning they always planned to return to China, aggravating whites even more as these men became nothing more than trespassers in America. After more violence erupted in Arizona and Nevada, in 1882, Congress finally limited the number of Chinese immigrants. But this law was full of loopholes and the immigration question was more confusing than ever.

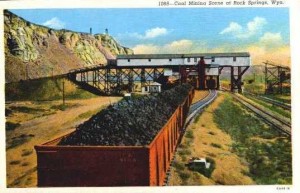

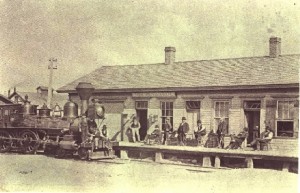

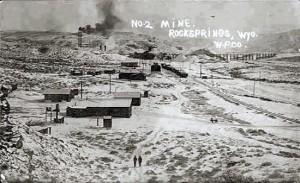

Coal was the main reason the railroad followed the route it did across southern Wyoming. The trains ran on coal from rich Union Pacific coal mines in Carbon, Rock Springs, and Almy, Wyoming.

Coal was the main reason the railroad followed the route it did across southern Wyoming. The trains ran on coal from rich Union Pacific coal mines in Carbon, Rock Springs, and Almy, Wyoming.

The Union Pacific, in financial trouble, saved money by cutting miners’ pay, and the miners and their families were required to purchase food, clothes, and tools only at the company’s stores where prices were much higher than in the surrounding towns. There were strikes about the wage cuts and about having to shop in the company stores.

In 1871, after one strike, the company brought in Scandinavian miners eager for work and willing to work for less and follow the rules. In 1875, after another strike Chinese workers were brought in for the same reason. By 1885, there were nearly 600 Chinese and 300 white miners working in Rock Springs.

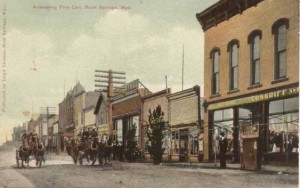

The whites, mostly Irish, Scandinavian, English and Welsh immigrants, lived downtown Rock Springs. The Chinese lived in what was called Chinatown on the other side of a bend in the railroad tracks and across Bitter Creek. There, the Chinese miners lived in small wooden houses the company built for them. Other Chinese ran businesses, herb stores, laundries, noodle shops, social clubs, and lived in shacks they built themselves.

Although they worked side by side the language barriers and fact that the white and Chinese miners lived separately meant each knew very little about the other. This ignorance, on both sides, made it possible for each race to think of the other as not entirely human.

Adding fuel to the fire, because the Chinese were willing to work for lower wages, everyone’s wages remained low. White miners resented it, and joined a new union, the Knights of Labor. In 1884, the Union Pacific told mine managers in Rock Springs were told to hire only Chinese.

In the summer of 1885, there were scattered threats against and beatings of Chinese men in Cheyenne, Laramie and Rawlins. Posters were hung in railroad towns warning Chinese to leave Wyoming Territory. Company officials ignored these threats and direct warnings by the Knights of Labor. Resentment and hostility continued to boil throughout the mining community.

On September 2, 1885, a fight broke out between white and Chinese miners in the No. 6 mine. A Chinese miner was fatally wounded with blows of a pick to the skull. A second Chinese miner was badly beaten before a foreman arrived and stopped the violence. Instead of going back to work, white miners went home and grabbed guns, hatchets, knives and clubs. The armed miners gathered on the railroad tracks near the No. 6 mine, north of Chinatown. Some made an effort to calm things down, but most moved to the Knights of Labor hall. They held a meeting, then went to the saloons where miners from other mines began gathering, as well. Sensing an increasing tension, saloon owners closed their doors.

It was a Chinese holiday, so many of the Chinese miners had stayed home from work and were unaware of the spark about to catch fire.

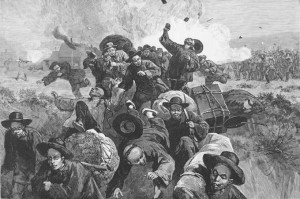

Shortly after noon, 100 to 150 armed white men, mostly miners and railroad workers, convened again at the railroad tracks near the No. 6 mine. Women and children started joining the group. The mob divided at 2:00p.m. Half moved toward Chinatown across the plank bridge over Bitter Creek. Others approached by the railroad bridge, leaving some behind at both bridges to prevent Chinese from escaping. A third group walked up the hill toward the No. 3 mine, north and on the other side of the tracks from Chinatown, leaving Chinatown completely surrounded.

At the No. 3 mine, white men shot Chinese workers, killing several. The mob moved into Chinatown from three directions, pulling Chinese men from their homes and shooting others as they ran into the street. Many Chinese fled, dashing through the creek along the tracks or up the steep bluffs and out into the hills beyond. A few terrified Chinese ran straight for the mob and met their deaths at the hands of white men, women and children.

The mob moved through Chinatown, looting stores, shacks and houses and then setting them on fire. More Chinese were driven out of hiding by the flames and were killed in the streets. Still others burned to death in their cellars. And still others died that night out on the hills and prairies from thirst, the cold and their wounds.

The mob left Chinatown burning and confronted the company bosses telling them it would be in their best interest to leave Rock Springs on the next train. They did. The sheriff of Green River, 14 miles away, learned of the killing and rushed to Rock Springs on a special train, but when he arrived no one would join him in a posse, and all he could do is join a few men to protect the company buildings from fire.

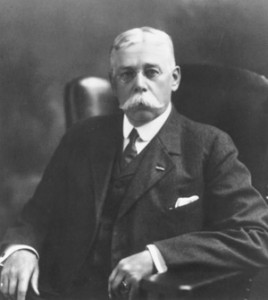

In Cheyenne, Territorial Governor Francis E. Warren learned of the murders late in the afternoon. Union Pacific officials took a special fast train all the way from Omaha, Nebraska (company headquarters) and arrived in Cheyenne at midnight. Warren joined them on the train and they all arrived in Rock Springs at daybreak on September 3.

afternoon. Union Pacific officials took a special fast train all the way from Omaha, Nebraska (company headquarters) and arrived in Cheyenne at midnight. Warren joined them on the train and they all arrived in Rock Springs at daybreak on September 3.

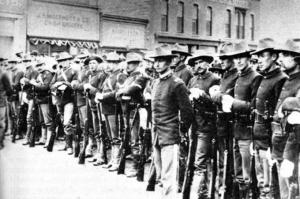

Warren appeared to be the only person who knew what to do. He sent telegrams to the Army and to President Grover Cleveland asking for federal troops to restore order. At Warren’s suggestion, the company train ran slowly along the tracks between Rock Springs and Green River, taking stranded Chinese miners aboard and giving them water, food and blankets.

In Rock Springs, Warren met with more company officials and then with the white miners. The miners demanded that no Chinese ever again be allowed to live in Rock Springs, and that no one would be arrested for the murders and burning. They said anyone objecting to these demands risked being hurt or killed.

To show he was unafraid, Warren left the railroad car several times during the day and made a show of walking back and forth on the depot platform. The people, now quiet and orderly watched him and nothing happened.

To show he was unafraid, Warren left the railroad car several times during the day and made a show of walking back and forth on the depot platform. The people, now quiet and orderly watched him and nothing happened.

Uinta County Sheriff J.J. LeCain in Evanston, Wyoming was sweating bullets. Hundreds of Chinese miners lived there, too, and worked in the coal mines at nearby Almy. White miners had left work, and armed mobs were in the streets of Almy.

LeCain telegraphed Governor Warren. With no territorial militia to command and no word about federal troops, there wasn’t much Warren could do, but to go to Evanston. He arrived the morning of September 4. LeCain deputized 20 men who barely managed to maintain order. On the fifth, a small detachment of troops arrived in Rock Springs. On the sixth, the striking white miners at Almy warned the Chinese if they went to work they wouldn’t leave the mines alive. Troops escorted the Chinese from their camp to the much larger Chinatown in Evanston. Although, the company assured the Chinese their property in Almy would be safe, as soon as they were gone whites looted their homes.

Most Chinese wanted was to get out of Wyoming as soon as possible. Ah Say, leader of the Rock Springs’ Chinese community, asked for railroad tickets. Company officials refused. Then he asked for the two months back pay the company owed Chinese workers. Again the company refused.

Over two hundred white citizens of Evanston presented Governor Warren a petition asking for the Chinese to be paid off so they could leave. Warren refused, saying it was a matter between the company and its employees. This was a risky decision considering things were ready to explode in Evanston.

Finally, more troops arrived in Rock Springs and Evanston nearly a week after the first killing. On September 9, under the protection of armed guards 600 Chinese in Evanston were taken to the depot and loaded on boxcars and told they were headed for San Francisco and safety. Without their knowledge, however, a special car carrying Warren and top Union Pacific officials was attached to the back of the train with 250 soldiers on board.

The train left Evanston heading east, not west, arriving in Rock Springs that evening. An angry crowd of white miners gathered. So the train continued a little farther, stopping just west of the ruins of Chinatown. The boxcar doors opened, and the Chinese realized they’d been tricked.

Climbing out of the boxcar they saw what little was left of the homes many fled in panic a week before. Chinatown was gone. Even more horrifying, bodies still littered the streets. Some had been buried by the coal company, but about a dozen had not. Many were in pieces, “mangled and decomposed being eaten by dogs and hogs.” Compounding this horror, the Union Pacific owners expected the miners to bury their dead, put the nightmare of this abomination behind them and get back to work. Until new houses could be built, they were expected to live in the boxcars.

For many days, the fearful Chinese miners would not go back to work. Again they asked for passes to California or their back pay, and again they were refused. The company store refused to sell goods to the Chinese who were not working and threatened to evict them from their temporary homes. About 60 fled Rock Springs by whatever method they found. The rest surrendered, and returned to work.

For many days, the fearful Chinese miners would not go back to work. Again they asked for passes to California or their back pay, and again they were refused. The company store refused to sell goods to the Chinese who were not working and threatened to evict them from their temporary homes. About 60 fled Rock Springs by whatever method they found. The rest surrendered, and returned to work.

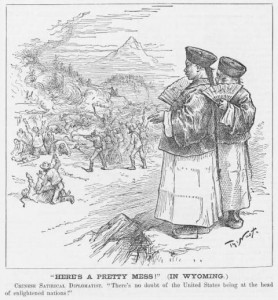

Sixteen white miners were arrested and released on bail. Though the killing had been done in daylight, no one could be found who would testify to seeing the crimes committed. No charges were filed.

In all, 28 Chinese were killed, 15 wounded and all 79 of the shacks and houses in Rock Springs Chinatown were looted and burned. Chinese diplomats in New York and San Francisco drew up a list of damages totaling $150,000. Congress, under pressure from President Cleveland, agreed to reimburse the miners. Many Chinese gradually left Wyoming throughout the following decades.

In Rock Springs, federal troops built Camp Pilot Butte between downtown Rock Springs and Chinatown to prevent further violence and stayed for 13 years.

Because of Governor Warren’s decisive courage in the first days after the riot, many more killings were avoided. However, Warren refused to help with the back-pay question and played a role in tricking the Chinese onto the train that took them back to Rock Springs, therefore not resolving the issue in the best interest of those victimized, or even the white miners.

After all was said and done, the Union Pacific was able to keep a large supply of Chinese miners around, making sure coal kept flowing and the wages could be kept low. This is what the Union Pacific wanted all along, leaving only one winner and hundreds of losers at the end of the violence.

I know, Cookie, pass that whiskey on over. Cookie and me, it sours our stomach to see such a thing happen in our fine State, so we’re hanging our heads a little lower.

But on a more positive note so we don’t leave ya draggin’, Rock Springs later became a bit of a meltin’ pot with over 78 nationalities represented, and livin’ peaceably (for the most part) together.

Wish I could say our next visit was gonna be more cordial like, but…Well y’all will just have to hold onto yer hats!

SOURCES:

http://www.wyohistory.org/essays/rock-springs-massacre

http://www.ghostcowboy.com/node/118

http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5042

http://www.wwcc.cc.wy.us/wyo_hist/chinese.htm

Wonderful post. I love how much research you put into this.

Thanks so much, Ella. Glad you stopped by and found the post of interest.

–Kirsten Lynn