Folks we’re likely to give those mules whiplash goin’ north than south only to whip back north, but I’ll try to keep us on a straighter trail the next few weeks.

Anywho, this week we’re turnin’ the wagons to Montana Territory and THE BATTLE OF THE LITTLE BIG HORN!

But we can’t go rushin’ into things and right into the middle of the battle (we all know how  that kind of rash action faired for Custer) Don’t get your petticoats in a bunch, we’ll get there, but first let’s take some side trails to northern Wyoming and South Dakota.

that kind of rash action faired for Custer) Don’t get your petticoats in a bunch, we’ll get there, but first let’s take some side trails to northern Wyoming and South Dakota.

The Bozeman Road enraged the Sioux and Cheyenne from it’s opening in 1863-64, because it crossed the Powder, Tongue, and the Big Horn rivers, lands they and their Crow enemies claimed as prime hunting grounds. Teton Sioux, Cheyenne and Northern Arapaho warriors allied to defend this territory, first in an attack at Platte Bridge Station, July 1865, and then against the troops brought against them. Hostilities escalated when Colonel Henry Carrington and his infantry headed for the Powder River, leading Red Cloud (the most powerful of the Sioux Chiefs) to lead the majority of Indian leaders to walk away from peace negotiations at Fort Laramie to return and defend their lands.

Carrington and his men established three forts in the area, Fort Reno, Fort Phil Kearny, and Fort C.F. Smith. Carrington’s troops quickly found themselves in an impossible situation with low morale and vastly outnumbered by the Indians. Red Cloud’s warriors closed in and placed the forts under siege with Fort Phil Kearny facing the worst of it.

In December 1866, a brash and reckless officer Captain William J. Fetterman took eighty-one men out of the fort to protect a wagon train and impetuously followed warriors led by a young Sioux war chief, Crazy Horse. Within forty minutes Fetterman and his men where dead. The Fetterman massacre shocked the nation and more troops were sent to the area to build a stronger fort, Fort Fetterman. Violence escalated and by 1867 the government realized it must vastly increase troops on the Bozeman Road or abandon it.

In the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, the Sioux seemingly got what they wanted. Red Cloud refused to discuss terms until the soldiers left the hated forts. The Bozeman Road was closed, the forts closed, with the promise of no new posts in that area. In line with the new policy of “concentration” the commissioners persuaded the chiefs to accept a reservation centering on the Black Hills and consisting mainly of today’s South Dakota west of the Missouri River. It must be noted that the Powder, Tongue and Big Horn areas, where Red Cloud had just won his war, were not part of the reservation. This area became unceded Indian lands, closed to general white entry, available for seasonal hunting, but not permanent occupation by the Indians.

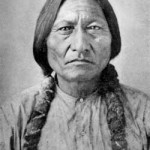

This treaty, like others before it, was only a temporary peace. Red Cloud and most of the older chiefs went on the reservation, but many younger Sioux leaders, like the Hunkpapa chief, Sitting Bull and the Oglala Crazy Horse, refused to accept the decision. These “nontreaty” Indians kept their bands in the unceded lands. Treaty commissioners expected these bands to be forced to the reservation when buffalo hunting declined. But these Sioux adamantly refused to settle on reservations and ventured farther north into the Yellowstone territory to hunt, making white settlers uneasy.

While things in the Yellowstone remained static for the most part, things in the Black Hills were building steam like an out of control locomotive headed toward a cliff. Rumors of gold spurred white men into the sacred Black Hills, lands clearly defined within the 1868 reservation. Men hungry for gold and good agricultural lands poured into this area.

In 1874, an officer hungry for glory, Colonel George A. Custer threw coal into the engine as  he led an “expedition” into the lands and sent back reports of a land heavy with gold and ripe for agriculture. And although Indians killed some and the army half-heartedly threw out others, still settlers came by the thousands. The 1875 gold boom made a travesty of the 1868 treaty and brought to a boil the situation with the Sioux. As more and more whites flooded the area the Indians left the corrupt agencies and headed west to join the nontreaty bands.

he led an “expedition” into the lands and sent back reports of a land heavy with gold and ripe for agriculture. And although Indians killed some and the army half-heartedly threw out others, still settlers came by the thousands. The 1875 gold boom made a travesty of the 1868 treaty and brought to a boil the situation with the Sioux. As more and more whites flooded the area the Indians left the corrupt agencies and headed west to join the nontreaty bands.

President Grant and policy makers far removed from the lands further complicated the issues. While passively allowing settlers into the Black Hills region, military force would be used to drive the Sioux and Cheyenne out of the unceded lands and back to the reservations.

Early December 1875, the Indian Bureau sent messengers to the bands in southeastern Montana and northeastern Wyoming, ordering them to return to the reservation by the end of January 1876. First, if you look at the timeline the order did not give the tribes enough time to comply, but it did not matter as the Indians had decided to stand and fight in any case. The United States Army officially called these bands “hostiles.”

The army eagerly made its first move against these hostiles in March 1876. General George Crook, who proved himself against the Apache in Arizona led 900 men north from Fort Fetterman, Wyoming. Facing subzero weather the first confrontation “Battle of Powder River” accomplished almost nothing. Even though a large band of Sioux was captured the army was unable to hold or destroy the camp. Crook returned to Fort Fetterman.

From his Chicago headquarters, General Phil Sheridan, developed a spring-summer three pronged campaign to corral the Sioux and Cheyenne. Three large armies would be sent into the unceded lands with the hopes at least one would engage the hostiles and defeat them. The “Montana Column” began moving down the Yellowstone in April 1876, with 450 infantry from Fort Shaw and Fort Ellis. Their commander was Colonel John Gibbon and their assignment was to block any Indian movement north or west of the Yellowstone. The “Dakota Column” left Fort Abraham Lincoln near Bismarck in mid-May under the command of General Alfred Terry. They moved across the Dakota plains and up the Yellowstone Valley. Among Terry’s column was the 700 man Seventh Cavalry under Colonel George A. Custer.

Custer was already a national hero for actions during the Civil War and as a dashing Indian Fighter. Originally, he was supposed to command the entire Dakota Column, but was removed from command when he testified against President Grant’s brother regarding the corruption of the Indian Services. At the last minute he was allowed to go along with the column and command the Seventh. Historians speculate Custer may have acted as he later did at Little Big Horn in an attempt to recover his glorious reputation he believed Grant tarnished.

While the Montana and Dakota columns moved toward a rendezvous on the lower Yellowstone, General Crook again led the army north from Fort Fetterman. Crook, Gibbon and Terry had only a general idea where the Indians where and how many there might be. Throughout the spring of 1876, bands of Sioux and Northern Cheyenne fled the reservation and joined the hostile camps near the Rosebud and Little Big Horn rivers. By June, their villages may have housed as many as 15,000 people, including three to four thousand warriors.

The three advancing columns were forced to act somewhat independently since communications were slow and unreliable. Crook encountered the Indians first. On June 17, his men paused on Rosebud Creek, a large Sioux-Cheyenne force under Crazy Horse, attacked them. It was a helter-skelter attack and counterattack ending when the Indians withdrew. Crook and his men withdrew, as well, back to Goose Creek. Crazy Horse moved to join their allies. This battle effectively removed Crook’s column from the campaign.

Terry and Gibbon converged on the Yellowstone. They had no idea about Crook’s location. They chose a sensible strategy of attempting to entrap the Indians from both the north and south. They would send Custer’s swift Seventh Cavalry on a sweep southward up the Rosebud and then across and down the Little Big Horn. Meanwhile, they would move the slower infantry southward up the Big Horn and then up its Little Big Horn tributary. Both armies should reach the Indian village on June 26, 1876. Terry gave Custer considerable discretion if the Indians seemed likely to escape.

June 22, Custer rode up the Rosebud. On June 24, he made his first controversial decision. Instead of following Terry’s order, he pursued and Indian trail westward before reaching the upper Rosebud. Driving his men to exhaustion on a night march, Custer reached the divide between the two streams, at dawn June 25, and his scouts reported smoke of an enormous encampment. Whether to gain all glory, or to hit the Indians before they could scatter, or both, Custer decided not to wait for Terry and the 26th rendezvous date. He failed to acknowledge the immensity of the Indian gathering, even though his terrified scouts warned him. The Seventh, in his vain opinion, could whip any number.

June 22, Custer rode up the Rosebud. On June 24, he made his first controversial decision. Instead of following Terry’s order, he pursued and Indian trail westward before reaching the upper Rosebud. Driving his men to exhaustion on a night march, Custer reached the divide between the two streams, at dawn June 25, and his scouts reported smoke of an enormous encampment. Whether to gain all glory, or to hit the Indians before they could scatter, or both, Custer decided not to wait for Terry and the 26th rendezvous date. He failed to acknowledge the immensity of the Indian gathering, even though his terrified scouts warned him. The Seventh, in his vain opinion, could whip any number.

Mid-day, Custer’s troops advanced down Reno Creek, out of sight from the Indian camp, the stream the Indians called the “Greasy Grass.” Custer divided his command into three units. Three troops under Captain Frederick Benteen to scout the hills west of the village, hoping Benteen could contain an Indian retreat. Major Marcus Reno, was ordered to cross the Little Big Horn with three more troops, and strike the camp at its southern end. Custer would retain the remaining five troops and skirt the bluffs to the right of the village and attack the center.

When Reno hit the near end of the enormous village, the Indians did not panic and rallied under Chief Gall and rushed their attackers. Reno tried and failed to form a defensive skirmish line. He led his men in a disorganized and bloody retreat back across the river and dug in on the bluffs there. Benteen’s returning force soon joined what was left of Reno’s, with Benteen taking over for the distraught Reno.

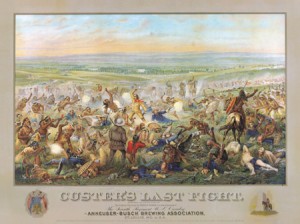

Unaware of these developments, Custer emerged from the bluffs to the east of the village and attempted to cross the river and attack it. But Gall’s warriors, having left Reno’s force, moved across the stream and attacked Custer instead. The colonel retreated up the ridges, but it was too late. More warriors joined Gall, and Crazy Horse led another attack flanking from the north. The Indians overwhelmed Custer’s skirmish lines, and within a half-hour wiped out his command. While they celebrated a great victory, the Indians kept Reno and Benteen under siege until evening the next day. Aware that more soldiers were coming they dispersed. Terry and Gibbon arrived at the battlefield on June 27, 1876. They buried more than two hundred and sixty dead and prepared Reno’s and Benteen’s wounded for removal to the steamboat Far West.

News of the “Last Stand” blazed across newspapers throughout the country in early July 1876. Highly inaccurate accounts of “the massacre” disrupted Fourth of July celebrations of the nation’s centennial, and sent Americans poring over maps of Montana Territory. Custer became the legend and hero he always desired being, and generations of schoolchildren learned of his daring actions, but never of his impetuous recklessness. And every western saloon, it appeared, displayed a romantic Anheuser-Busch painting of the battle. Custer’s wife, Libby, was the greatest proponent of spreading his legend, and it is believed it was in her honor that those who knew best of his actions on that day, kept their mouths closed until after her death.

The Battle of the Little Big Horn was in no way decisive. The Indians won a significant victory, but this victory only postponed their ultimate and tragic defeat. More troops descended on the plains at the call for unconditional surrender.

The Battle of the Little Big Horn was in no way decisive. The Indians won a significant victory, but this victory only postponed their ultimate and tragic defeat. More troops descended on the plains at the call for unconditional surrender.

Brave chiefs and warriors like Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse continued to resist. But in 1877, starving and demoralized Sioux and Northern Cheyenne bands surrendered. Even the great Crazy Horse gave up in early May. By autumn1877, the conquest of the proud Sioux and Northern Cheyennes was complete. Their brave “stand” against Custer all but forgotten and diminished by the Custer propaganda until cooler heads removed from the time and prejudice could provide a complete picture to the events in June 1876.

So take your young’uns on up to Montana where every June reenactors bring history to life. This year y’all can catch a full color reenactment on June 22, 23, or 24th. Iffin’ ya want to join the action contact www.custerslaststand.org and ride into battle with Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, or with George A. Custer’s Seventh Cavalry.

So take your young’uns on up to Montana where every June reenactors bring history to life. This year y’all can catch a full color reenactment on June 22, 23, or 24th. Iffin’ ya want to join the action contact www.custerslaststand.org and ride into battle with Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, or with George A. Custer’s Seventh Cavalry.

The other forts and battlefields mentioned in this post can be visited, as well. In some cases, the buildings are gone, but there are still markers and signs you can follow. And don’t forget to visit The Custer Battlefield Museum in Garryowen, MT.

Toss the young’uns in the wagon and continue their learnin’. Heck, they won’t even know this is all that yuck from their ol history books, and they’ll learn somethin’ before they realize what happened. And ya know y’all just might learn somethin’, too.

See ya on the trail, and watch how ya drive those mules! Last time ya almost ran clear into Cookie’s grub wagon, he liked to ‘ave turned the air blue.

**Crazy Horse is not pictured in this post as I could only find pictures thought to be the Sioux warrior

Source:

Malone, Michael P., Lang, William, Roeder, Richard. Montana: A History of Two Centuries. University of Washington Press. Seattle. 1976.

My own essay written in 1995 while attending Montana State University-Billings, and plaques on trails of the various battle listed from my trips to these locations.

Another great post, Kirsten. I remember visiting the battlefield and several of the fort sites when I was just a child. I was fascinated by history — especially the history of westward expansion — even then. Montana has some beautiful country, but the thing I remember most about living there is how snow drifts would reach the roofs of single-story houses in the winter. Imagine what living in that kind of weather must have been like for the Indians and soldiers!

Thank you, Kathleen. It’s always a pleasure having you stop by the campfire. It is unbelievable to think what the weather in Montana and Wyoming must have been like for the Indians and soldiers, and no wonder many campaigns were abandoned due to subzero temperatures. I remember when I attended college in Billings and walked to my early classes in wind chills of -70 (I’m not exaggerating), and couldn’t imagine not walking into a building with the heat blaring.

This is a great post. That’s not an area of the country I’ve had a chance to visit yet, but I hope to one day. Such a sad story – for both sides.

Thanks so much, Ally! You’re correct it is a sad story for both sides, as even though the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne won the day it was only a matter of time before they were forced onto the reservations, and then of course the horrible loss of life of those men who followed Custer into a slaughter. I hope you will be able to visit the West, so much history around every corner.

Great post, Kirsten! I’ve visited many Civil War battlefields, but all on the East coast. This sounds like a fascinating place to visit.

Thank you, Susan! It really is a fascinating place, and as I briefly mentioned at the end they have a nice museum you can go through first to see artifacts from the battle and those who were a part of it. If you like visiting battlefields, I think you would find this interesting. And unlike the battlefields in the East, the terrain hasn’t changed much at all.

Thanks for an interesting and educational post Kirstin, and it was well written too. Good job. I love westerns and beings I’m part Native American, I’d love to go to this site someday and participate in the re-enactment.

Debby, I hope you will get the opportunity to participate in the re-enactment. I never have, but it looks like an interesting way to learn all about the battle and those who fought it. Thank you for your kind words.

What a very informative post. I learned a lot. Would love to get there some day.

Thank you, Anne. Hope you do get a chance to visit the battlefield.

Great history blog. I set one of my books in Montana. People sometimes forget about this state when they think of the Old West but actually so much happened there.

Hi Sharla! Thanks so much for stopping by. You’re right, so many focus on Texas, Arizona, New Mexico and the like, but up North Montana was far from tame and a huge part of the history of the Old West.

I love your posts, Kirsten! I learn something new every week.

Thanks so much, Cec! It’s so nice of you to say, and makes posting worthwhile when someone is learning something from them.