I tell ya folks Cookie and me have been whippin’ up some more trails to blaze and wild paths to follow!! Fact is we’ve turned the wagon toward our next destination, but then the ol’ coot reminded me I promised to tell y’all about Chief Washakie, so he stopped the wagon! Fact is, Cookie just wanted another piece of Ma’s pie! For that trick I offered the Shoshone thirteen horses to take the codger, they countered, offerin’ sixteen for me to keep ‘im! Dagnabbit!!

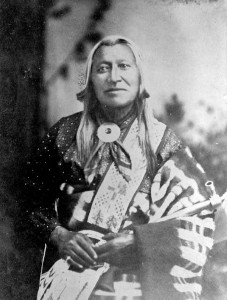

Failed negotiations aside, think I told y’all at our last campfire ‘while back each state got to choose two people whose statue would go into the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. I introduced y’all to the first person honored from Wyoming, Mrs. Esther H. Morris. Now sit on down ‘round the fire and let me introduce ya to the second person Wyoming honored with a statue, the great Shoshone leader, Chief Washakie!

Chief Washakie’s early life still holds many mysteries. The year of his birth and the year he joined the Shoshone tribe have both been speculated upon by numerous Indian agents, religious leaders and historians. An early biographer, Grace Raymond Hebard records the year of his birth as 1798, however, his gravestone is inscribed with an 1804 date. Washakie, in an interview with an Indian Agent at the Wind River Reservation Captain Patrick H. Ray provides some hints that would place his birth closer to 1808 or 1810. Regardless of the year Washakie was born, or joined the Shoshone tribe he became a fierce warrior and a great leader for the Eastern Shoshone.

Even the name by which he would be widely known has been translated in various ways. Although, it apparently dealt with his tactics in battle. One story details a large rattle Washakie devised by placing stones in an inflated and dried balloon of buffalo hide which he tied on a stick. He carried the device into battle to frighten enemy horses, earning the name “The Rattle.” Another translation of Washakie is “Shoots-on-the-Run,” or “Shoots-buffalo-on-the-run.”

Originally named Pinaquana (smell of sugar), he was born in his father’s Salish (Flathead) tribe. His mother was Lemhi-Shoshone. When Washakie was just a boy, his tribe was attacked by Blackfeet and his father was killed. The survivors of the attack scattered with Washakie’s mother taking him and his siblings to the Lemhi-Shoshone. Later his mother returned to the Flathead, but Washakie and his sister stayed with the Lemhis. At about the age of sixteen Washakie joined a band of Bannocks. The Bannocks, linguistically related to the Shoshones, were trading and hunting partners with the Shoshone tribe and frequently joined them on massed buffalo hunts in Montana and Wyoming. This particular band considered the Green River basin area of southwestern Wyoming their home.

Originally named Pinaquana (smell of sugar), he was born in his father’s Salish (Flathead) tribe. His mother was Lemhi-Shoshone. When Washakie was just a boy, his tribe was attacked by Blackfeet and his father was killed. The survivors of the attack scattered with Washakie’s mother taking him and his siblings to the Lemhi-Shoshone. Later his mother returned to the Flathead, but Washakie and his sister stayed with the Lemhis. At about the age of sixteen Washakie joined a band of Bannocks. The Bannocks, linguistically related to the Shoshones, were trading and hunting partners with the Shoshone tribe and frequently joined them on massed buffalo hunts in Montana and Wyoming. This particular band considered the Green River basin area of southwestern Wyoming their home.

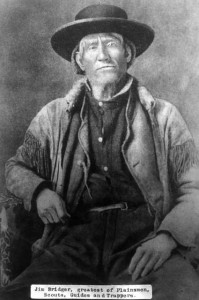

One of the relationships that provide clues to Washakie’s birth year is his friendship with  Jim Bridger. Washakie, in his interview with Ray, stated he met Bridger when he was sixteen after joining the Shoshone tribe and that Bridger was a few years older than Washakie. Bridger who was born in 1804 did not enter Shoshone country until 1824. It was during Bridger’s time with William Ashley’s Rocky Mountain Fur Trade Company and at the rendezvous in the vicinity of Henry’s Fork of the Green River when the two met. Washakie then hunted and trapped with Bridger attending rendezvous with the famous trapper and explorer. This is also the time when Washakie cast his lot with a band of Shoshone who claimed the Green River and Bear River regions there Washakie lived in proximity for many years with fur trappers and traders. He learned their mannerisms and languages, English and French. He traded with these men and earned a reputation as a friend among the whites.

Jim Bridger. Washakie, in his interview with Ray, stated he met Bridger when he was sixteen after joining the Shoshone tribe and that Bridger was a few years older than Washakie. Bridger who was born in 1804 did not enter Shoshone country until 1824. It was during Bridger’s time with William Ashley’s Rocky Mountain Fur Trade Company and at the rendezvous in the vicinity of Henry’s Fork of the Green River when the two met. Washakie then hunted and trapped with Bridger attending rendezvous with the famous trapper and explorer. This is also the time when Washakie cast his lot with a band of Shoshone who claimed the Green River and Bear River regions there Washakie lived in proximity for many years with fur trappers and traders. He learned their mannerisms and languages, English and French. He traded with these men and earned a reputation as a friend among the whites.

But while trapping and trading were valuable activities to the fur trappers these were not enough to gain prominence with Shoshone culture. In order to do this, young men had to prove themselves in battle. So at the same time Washakie was immersed in the fur trade, he also made war on the tribe responsible for his father’s death, the Blackfeet.

The first few raids into Blackfeet country, Washakie tells Ray he was young, unmarried and he followed another leader, until he gained enough prowess to lead other raids. One of the most remarkable things about each of the journeys to Blackfeet country was that Washakie and his fellow Shoshones started on foot from their Idaho or Wyoming base and attacked the Blackfeet near the Three Forks area or even farther east or north. There were two goals for each of these raids, first to steal horses, secondly, to take Blackfeet scalps.

By early 1830s, Washakie matured enough and had achieved enough acclaim in the raids on the Blackfeet to marry his first wife. Shoshone men typically married in their early to mid-20s, depending on their prowess as warriors and their economic viabilities as hunters. Shoshone women typically married at a younger age, usually fifteen or sixteen.

Washakie continued to maintain his hunting, trapping, trading, and warring activities from his home in the Green River, Bear River and Cache Valley throughout the 1830s and into the 1840s. During this time, the Shoshone bands were under the leadership of several powerful headmen who amassed over 2000 Indians in the buffalo hunting trips to the plains of Montana and Wyoming. These leaders were identified by trapper William A. Ferris as: Horn Chief, Iron Wristband, Little Chief, and Cut Nose. Cut Nose was the leader of Shoshones who intermarried and lived in a mixed Indian-White community in the Green River region. It is believed this was Washakie’s band.

Osborne Russell, another trapper, met Iron Wristband in 1834, and stated Iron Wristband was known as Pahdahewakunda and Little Chief was his brother. Little Chief was called Mohwoomha by the Shoshones. Making clear distinctions about Shoshone leaders proved impossible for white observers. To outsiders, it seemed as if certain leaders controlled thousands of people, but in reality, such men generally were leaders of specific events, such as annual massed buffalo hunts, rendezvous, or ceremonials such as the Sun Dance, not overarching rulers. Shoshones organized themselves into loose-knit family bands for various composition and size. The economics of providing food and fodder for thousands of Indians and their horses acted against maintenance of large-scale communities. Once large gatherings ended, Shoshones dispersed into more manageable and smaller groups of 10 to 150 people. Each of these had their own designated leaders, or headmen.

So, along with the leaders mentioned above, fur trappers noted other important warriors. Russell called three young warriors “the pillars of the nation and [men] at whose names the Blackfeet quaked with fear.” These three warriors were: Inkatoshapop, Fibebountowatsee, and Whoshakik. Whoshakik refers to the warrior we know as Washakie. Another trapper, William Hamilton, camped for part of 1843 with Washakie and noted the Shoshone warrior led hunting trips into Crow territory of the Big Horn River. In each account the trappers note Washakie’s friendly relationships with trappers and traders.

So, along with the leaders mentioned above, fur trappers noted other important warriors. Russell called three young warriors “the pillars of the nation and [men] at whose names the Blackfeet quaked with fear.” These three warriors were: Inkatoshapop, Fibebountowatsee, and Whoshakik. Whoshakik refers to the warrior we know as Washakie. Another trapper, William Hamilton, camped for part of 1843 with Washakie and noted the Shoshone warrior led hunting trips into Crow territory of the Big Horn River. In each account the trappers note Washakie’s friendly relationships with trappers and traders.

Trappers, like Jim Bridger, used their trade relationships to foster the “careers” of their friends. In 1849, Indian Agent John Wilson noted that Washakie, Mono, Wiskin, and Big Man were the main leaders. Wilson took his information directly from reports by Bridger. Washakie denied this in his interview with Captain Ray stating that Gahnacumah was the leader of his band and Washakie was the war chief. It is also of note that close to the same time Bridger elevates Washakie to that of a leader of the Shoshone, Washakie’s daughter, Mary, became Jim Bridger’s third wife. She was about 17 years old and Bridger was 46.

Whether Washakie was “chief” of the Shoshones or not, he quickly moved into that position in the eyes of white officials. The same year of Wilson’s report, he asked Washakie to help solve an intertribal feud over horse stealing between the Utes, Paiutes, and Shoshones. For the first time the federal government officially recognized Washakie as an important leader. The actual meeting took place in 1852. Before this meeting could take place, the government called a more important meeting to establish peace on the Plains between the Mandan, Sioux, Crow, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Blackfeet and other tribes in an attempt to provide safe passage for emigrants traveling the overland trails. Jacob Holeman, recently appointed Indian Agent for the newly created Utah Superintendent of the Office of Indian Affairs, thought other tribes whose lands were affected by the overland emigrants should also attend the meeting.

Holeman sent Bridger to gather the Shoshones and bring them to the council. This would not be an easy task, as the site of the meeting, on Horse Creek about 30 miles from Fort Laramie, was squarely in the enemy territory as far as Shoshones were concerned. The timing was off for the Shoshones, as well. It was August, when most Shoshones were on fall buffalo hunts. Bridger found the band that included Washakie camped along the Sweetwater River. The leader of the band, Gahnacumah was hunting buffalo and refused to attend the council. And to sour things further, a raiding party of Cheyenne attacked a small group of Shoshone hunters near the camp, killing two and stealing horses. The few leaders in camp immediately mistrusted the upcoming peace council and argued for three days. A desperate Bridger asked Washakie to take charge and resolve the issue. Washakie stated he: “called in all the young men who had been to war [with me]” and told them, “I was going to stay with the white men and they must make up their minds to go or to stay and they all said they would stay. There were a good many of them.” They also elected Washakie as their war chief.

As far as the whites were concerned this began Washakie’s chieftainship. Sixty to eighty warriors followed him to the Fort Laramie/Horse Creek council. There the Shoshones entered in full dress regalia that reportedly started their enemies scrambling for weapons thinking the Shoshones intended to attack. Despite their grand entrance, the Shoshones were excluded from official participation since the meeting was called for the Plains tribes only and the Shoshones resided primarily west of the Rocky Mountains. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, established territorial claims for the Plains tribes. The Indians guaranteed safe passage for settlers on the overland trails in return for an annuity of fifty thousand dollars for ten years. Also, the nations would allow roads and forts to be built in their territories. Although, left out of the council, Washakie adhered to the terms of the treaty and he played on this “friendship” with the whites to gain whatever advantages he could for his followers.

As far as the whites were concerned this began Washakie’s chieftainship. Sixty to eighty warriors followed him to the Fort Laramie/Horse Creek council. There the Shoshones entered in full dress regalia that reportedly started their enemies scrambling for weapons thinking the Shoshones intended to attack. Despite their grand entrance, the Shoshones were excluded from official participation since the meeting was called for the Plains tribes only and the Shoshones resided primarily west of the Rocky Mountains. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, established territorial claims for the Plains tribes. The Indians guaranteed safe passage for settlers on the overland trails in return for an annuity of fifty thousand dollars for ten years. Also, the nations would allow roads and forts to be built in their territories. Although, left out of the council, Washakie adhered to the terms of the treaty and he played on this “friendship” with the whites to gain whatever advantages he could for his followers.

Washakie was the clear leader of choice for white officials. There were other prominent Shoshone headmen, chiefs in their own right, who led various bands, but Washakie was the primary leader to whom whites turned for guidance concerning most of the buffalo-hunting Shoshones. As for Washakie, he learned the intricacies of negotiating within the white world from his long relationship with Jim Bridger and other trappers and traders. He used these skills to obtain goods, supplies, and food from government officials.

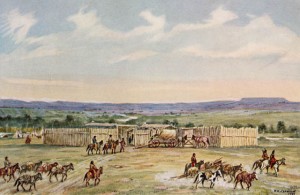

The pioneers who passed through his territory had tremendous impact on Washakie’s Shoshones. Washakie’s band was headquartered around Jim Bridger’s fort during the 1840s. In the early 1850s, following his rise to a more prominent role, Washakie’s activities remained centered around Fort Bridger and also Salt Lake City. Washakie had built trade relationship with Brigham Young, where the Shoshones traded buffalo hides and other game pelts for goods and supplies. By the mid-1850s the continuous flow of white settlers through this area disrupted life and hunting to such a great extent Washakie began to seek out areas where whites had not yet settled. He believed trading in Salt Lake was still important in the summer, but in late fall, Washakie’s Shoshones headed north to the Three Forks area of Montana for their buffalo hunts. If you’ll recall this is the place where Washakie had gained his prowess as a warrior against the Blackfeet. The band whose members formed the majority of the Plains-going Shoshones, made the change to their geographical range from the mid-1850s through early 1860s. Washakie’s plan was two-fold: first, it prevented factions within his band from raiding or killing white travelers, and second he could still lead his people to buffalo in relative safety without violating the territorial boundaries marked out by the Treaty of Fort Laramie.

The pioneers who passed through his territory had tremendous impact on Washakie’s Shoshones. Washakie’s band was headquartered around Jim Bridger’s fort during the 1840s. In the early 1850s, following his rise to a more prominent role, Washakie’s activities remained centered around Fort Bridger and also Salt Lake City. Washakie had built trade relationship with Brigham Young, where the Shoshones traded buffalo hides and other game pelts for goods and supplies. By the mid-1850s the continuous flow of white settlers through this area disrupted life and hunting to such a great extent Washakie began to seek out areas where whites had not yet settled. He believed trading in Salt Lake was still important in the summer, but in late fall, Washakie’s Shoshones headed north to the Three Forks area of Montana for their buffalo hunts. If you’ll recall this is the place where Washakie had gained his prowess as a warrior against the Blackfeet. The band whose members formed the majority of the Plains-going Shoshones, made the change to their geographical range from the mid-1850s through early 1860s. Washakie’s plan was two-fold: first, it prevented factions within his band from raiding or killing white travelers, and second he could still lead his people to buffalo in relative safety without violating the territorial boundaries marked out by the Treaty of Fort Laramie.

The 1850s also saw change in Washakie’s band. Shoshones and Bannocks of Idaho began more frequent campaigns of armed resistance to the invasion of their lands by emigrants and settlers. As a result, Washakie began to lose some of his followers, especially younger warriors who resisted Washakie’s continued friendship toward the whites. By 1858, Washakie began making overtures to white officials to set aside land specifically for the Shoshones. He first suggested land along Henry’s Fork, a tributary of the Green River near the border of Utah and Wyoming. Later, he proposed a reserve near the Uinta Mountains of northeastern Utah. But his negotiations led to gifts of food, clothing, and good will, but not a secured track of land for his people.

Spurred into action by the growing number of raids on settlers, government officials finally sought to set aside lands for the Shoshones and Bannocks. At the same time, Colonel Patrick Connor led a large-scale militia attack on a Shoshone winter camp near the Bear River. Connor’s attack led to the massacre of over 240 Indians. While Washakie was not at the camp near Bear River, when the government sought to make a treaty he was called to the negotiations at Fort Bridger along with ten other leaders. The Fort Bridger Treaty of 1863 set aside over 44,000,000 acres of land for “Shoshone country.” The land was east of the Wind River Mountains and north of the main immigrant trails through the Basin regions.

This agreement, like most during this time period, brought peace for a time between Shoshones and whites, but was riddled with problems. Settlers and emigrants now had free access to traditional Shoshone hunting grounds in the Fort Bridger, Bear River, and Salt Lake region, and started spreading up the Green River Valley. Therefore, Washakie and other Shoshone leaders were forced to increasingly turn to hunting in Crow territory, or even onto the Plains east of Powder River and the Big Horn Mountains. As a result, Shoshones became vulnerable to attacks by Crows, Cheyenne, Sioux, and Arapahos, all vying for the same hunting grounds. At the same time, as previously discussed in past posts, white prospectors were flooding into South Pass, Miner’s Delight, Atlantic City and farmers were claiming land near some of the tributaries of the Big Wind River. [See last week’s post on the Battle of Crowheart Butte for details on the escalation of violence between the Shoshone and Crow]

With violence between tribes escalating, the end of the Civil War, the building of the first transcontinental railway and more gold discoveries in South Dakota and Montana, a new round of negotiations with many of the Indian tribes was sparked in 1867 and continuing through 1868. Washakie took advantage of this situation upon hearing the Crow relinquished their claim on the Wind River he met with officials again at Fort Bridger and signed the Fort Bridger Treaty in 1868. This treaty created the Shoshone and Bannock Indian Agency in the Wind River Valley. Today, the Wind River Reservation is the only one in the United States which occupies land chosen by the tribe that lives there.

A treaty on paper did not create immediate benefits. Sioux warriors under Red Cloud continued to raid both whites and Shoshone towns and camps along the Wind River, making it too dangerous to make a permanent home there. The government, under Washakie’s petitions, established a military base at Camp Brown (later called Fort Washakie) to provide protection to the agency. By 1871, the first agency buildings had been erected, and Washakie and his Shoshones began to learn a new way of life. Washakie included demands for new schools, physicians, teachers, carpenters and other skilled craftsmen in his treaties with the government.

For the next 30 years, Washakie walked a thin line between adhering to the new demands placed on his people to become “civilized,” while at the same time maintaining traditional Shoshone ways. Through the 1870s he encouraged his children to attend agency schools, but still took them on fall buffalo hunts. [Again please refer to last week’s post for information on agency schools and Rev. Roberts] He moved from living in hide teepees to log houses, yet still led warriors into battle against the Sioux and Cheyenne in the U.S. Army campaigns of 1876. He insisted white officials abide by Shoshone council decisions regarding distribution of food, annuities, and supplies. He maintained his role as the spokesman for the tribe, but also respected the leadership of the various Shoshone bands who lived on the reservation. He refused to allow an Indian police force (who often served as spies for white officials) to be created through the 1880s stating, the Shoshone could police themselves and provide good order. He farmed a small plot of land, as an example to other Shoshones, and insisted white farmers and ranchers pay for the use of reservation lands in livestock or grazing fees.

For the next 30 years, Washakie walked a thin line between adhering to the new demands placed on his people to become “civilized,” while at the same time maintaining traditional Shoshone ways. Through the 1870s he encouraged his children to attend agency schools, but still took them on fall buffalo hunts. [Again please refer to last week’s post for information on agency schools and Rev. Roberts] He moved from living in hide teepees to log houses, yet still led warriors into battle against the Sioux and Cheyenne in the U.S. Army campaigns of 1876. He insisted white officials abide by Shoshone council decisions regarding distribution of food, annuities, and supplies. He maintained his role as the spokesman for the tribe, but also respected the leadership of the various Shoshone bands who lived on the reservation. He refused to allow an Indian police force (who often served as spies for white officials) to be created through the 1880s stating, the Shoshone could police themselves and provide good order. He farmed a small plot of land, as an example to other Shoshones, and insisted white farmers and ranchers pay for the use of reservation lands in livestock or grazing fees.

But changes were already in the air that would limit Washakie’s choices about keeping even part of their traditional ways. The Brunot cession of 1872 ceded nearly one-third of the reservation. Settlers in towns such as Lander, promoted more settlement in the “unoccupied” lands to be used for stockgrowing, hunting, and logging.

Washakie’s influence waned even more regarding reservation policies. The Arapahos, long-time enemies of the Shoshones, were moved to the reservation in 1878. Supposedly a temporary placement, the Arapahos became equal shareholders in the resources of the reservation. This severely limited Washakie’s ability to shape council decisions and limit the impact of official decisions. A more telling blow was the elimination of buffalo hunting as a mainstay of the Shoshone economy. As long as Washakie and the Shoshones could depend on buffalo as their main source of food and economic activity, they could thwart attempts of the Indian agents to turn them into farmers. The last buffalo were killed in 1885 and the Wyoming livestock industry expanded into Wind River country, curtailing off-reservation hunting access to other big game such as elk. This forced the Shoshone to pay more attention to farming, ranching and wage labor.

Washakie’s influence waned even more regarding reservation policies. The Arapahos, long-time enemies of the Shoshones, were moved to the reservation in 1878. Supposedly a temporary placement, the Arapahos became equal shareholders in the resources of the reservation. This severely limited Washakie’s ability to shape council decisions and limit the impact of official decisions. A more telling blow was the elimination of buffalo hunting as a mainstay of the Shoshone economy. As long as Washakie and the Shoshones could depend on buffalo as their main source of food and economic activity, they could thwart attempts of the Indian agents to turn them into farmers. The last buffalo were killed in 1885 and the Wyoming livestock industry expanded into Wind River country, curtailing off-reservation hunting access to other big game such as elk. This forced the Shoshone to pay more attention to farming, ranching and wage labor.

While changes and Washakie’s increasing age limited his power it did not end entirely. In the mid-1880s, Wind River Indian agents signed on Shoshones to the tribal police service, but Washakie named the men who would serve in these positions. He often nominated the Shoshone Indian employees for agency positions as teamsters, farmers, herders, etc. While younger men played increasingly important roles in Shoshone councils, Washakie was still the dominant voice well into the 1890s. His last major act took place in the 1896 Hot Springs land cessions, when Shoshones and Arapahos gave in to the demands of the government to sell a ten-square mile parcel of land at the northeast corner of the reservation. This parcel contained natural hot springs (present day Thermopolis). Washakie insisted that the springs remain open to all peoples; this condition is still honored today.

Washakie became ill in the winter of 1899 and succumbed to the illness on February 20, 1900. Buried with full military honors and with a funeral train that stretched for miles, Washakie’s death was a symbol, as his life had been, of the effort made to bring peace to disparate peoples, to listen to ideas and adapt to new ways while honoring the traditions of a proud people. No other leader emerged from the Shoshones who achieved his stature.

Over one-half of the adult males expressed their loss a few months after his death in a letter written to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs:

“Our Great Father: We your children The Shoshones, Would be pleased if you would appoint some one [sic] of our number to be our Chief or in some way give us a head. As you must know, that our old Chief Washakie is dead, and we are now left with out [sic] a head to look too. It is now with us like a man with many tongues all talking at once and every one of his tongues pulling every which way. We are feeling bad that things should be in such shape among us. So we leave it to you to say who shall be our chief, or you name any number say nine or eleven but we want you to say and we will abide by what you say.”

Suffice it say, the “Great Father” did not appoint a new chief. Instead, after many years of struggle, the Eastern Shoshones are now governed by a democratically elected Joint Business Council.

Folks, I tell ya that’s one heck of a history! Proud and heartbreaking all wrapped in one bedroll of a man who saw the need to adapt to new ways, while tryin’ to retain the honor and traditions of his people. The country as a whole could benefit from more men like Chief Washakie.

Folks, I tell ya that’s one heck of a history! Proud and heartbreaking all wrapped in one bedroll of a man who saw the need to adapt to new ways, while tryin’ to retain the honor and traditions of his people. The country as a whole could benefit from more men like Chief Washakie.

Next week folks we’ll be back ridin’ the rough trail over new ground. That is if I can get Cookie’s pie soaked behind back on the wagon and the horses can pull the extra weight…that’s right plum embarrassin’ jawin’ with the good Chief and you shovin’ pie down your gullet…

See y’all next time on the trail!!

SOURCES:

http://wyoarchives.state.wy.us/Research/Topics/FTopic.asp?SubID=4&nav=1&homeID=1

http://www.windriverhistory.org/exhibits/washakie_2/life.htm

Stamm, Henry E., IV. People of the Wind River: The Eastern Shoshones, 1825-1900. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999.

Good one, Kirsten. I’m always interested in learning more about the tribes and the chiefs. Thanks!

Thanks, Tanya! I’ve recently become more interested in the American Indian culture and peoples. I grew up in a small town right on top of the Wind River Reservation, and just always took the history of that area for granted. Now that I’m researching it, I can’t believe all the great history I missed. :o)

–Kirsten Lynn

What a great blog, Kirsten. Washakie’s always fascinated me–I’ve even used him as a secondary character in a couple of my stories. But I never knew the details of his life until reading this. Just wish I could have seen him as a young brave. Such a handsome older man must have been romance cover material in his younger days. 🙂

Thanks so much, Elizabeth! I agree about the romance cover material. 🙂 The earliest picture I found was the first I used, but even that was circa 1865. This was a fun blog for me, I don’t know what took me so long to look into the life of Washakie; now I’m trying to work him into a story. 🙂

–Kirsten Lynn

I loved the pictures. What an interesting character.

Ella, Thanks so much for stopping by! So glad you enjoyed the pictures. Washakie was a very complex and interesting person.

–Kirsten Lynn

I’ve read and learned quite a bit about Chief Washakie, and one fact continues to amaze me…how many of my and my husband’s progenitors of the pioneer and early 1900s era he directly influenced, benefited, crossed paths with, or even had one of his children/grandchildren (or relative) raised by–it seems there are more than a few. It would be intriguing to follow one of these stories to see how many generations have been influenced and enriched by Washakie’s own heritage and also his tribal Wind River Shoshone heritage. His decisions were wise and far reaching beyond what most would have ever realized back in those days. I’ll be interested to hear about whatever you write that concerns the heritage Chief Washakie left all of us in this northwestern part of the U.S.A. “Behne.”