Folks I apologize, but Cookie is takin’ his own sweet time gettin’ our supplies here at South Pass so we’re hold up for a bit. Shouldn’t have let the man play that first game of billiards…So while the ol’ coot is loadin’ up the wagon I thought we might jaw a bit with a woman who made history in Wyoming and the country. Ya know Wyoming isn’t called the Equality State just cause we thought it was cute…

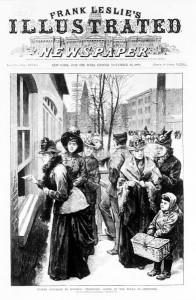

Why the Wyoming Territorial legislature passed the first law giving women the vote is a question that is still somewhat of a mystery to historians. Whether a ploy to bring attention to the territory, or as a way for Democrats to counter the predominately Republican voting Black community, or a ploy to promote partisan legislation all of these theories were bantered about in 1869, and the question remains unanswered today. Some even suggested the bill was a joke intended to embarrass Governor Campbell, however this theory was easily dismissed with the extent and seriousness with which it was defended and debated. Whatever led to the passage of women’s suffrage in 1869 (the first law of its kind in the nation), the territory later insisted upon retaining its woman suffrage law even if it jeopardized its application for statehood. And in 1890, Wyoming became the country’s first state to allow women the right to vote.

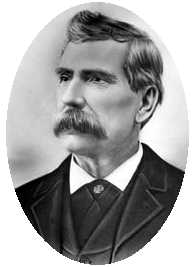

As mentioned in the post on South Pass, William H. Bright introduced the bill giving women the vote. But before Wyoming delegates assembled in Cheyenne in 1869, women suffrage bills were introduced in three Western legislatures, Washington in 1854, Nebraska in 1856, and Dakota in 1869, all defeated. Wyoming legislators were well aware of the discussion over women’s suffrage as many had recently moved from Midwestern states. In addition to the knowledge these delegates brought with them, two women delivered speeches in Cheyenne in support of women’s suffrage, Anna Dickinson at the courthouse, and Redelia Bates to the legislators.

As mentioned in the post on South Pass, William H. Bright introduced the bill giving women the vote. But before Wyoming delegates assembled in Cheyenne in 1869, women suffrage bills were introduced in three Western legislatures, Washington in 1854, Nebraska in 1856, and Dakota in 1869, all defeated. Wyoming legislators were well aware of the discussion over women’s suffrage as many had recently moved from Midwestern states. In addition to the knowledge these delegates brought with them, two women delivered speeches in Cheyenne in support of women’s suffrage, Anna Dickinson at the courthouse, and Redelia Bates to the legislators.

Council Bill #70 “…an act to grant to the women of Wyoming Territory the right of suffrage and to hold office,” was read two times before being sent to committee, which quickly recommended “do pass.” After passing the Council on November 30, the bill went to the House and endured much debate with another South Pass City resident, Benjamin Sheeks, leading the opposition to women’s suffrage. After much debate, and proposed additions and replacements to the bill (all failed) CB #70 passed into law with Governor Campbell signing the bill into law, December 10, 1869.

Be it enacted by the Council and House of Representatives of the Territory of Wyoming:

Sec. 1. That every woman of the age of twenty-one years, residing in this territory, may at every election to be holden under the laws therof, cast her vote. And her rights to the elective franchise and to hold office shall be the same under the election laws of the territory, as those of electors.

Sec. 2. This act shall take effect and be in force from and after its passage.

While signing the bill Campbell noted that women were as capable as men in exercising the good judgment required to vote. He also noted women who own property must be taxed, making women’s suffrage necessary to ensure fair representation in the creation of tax laws. News spread throughout the nation that Wyoming had become, “the first place on God’s green earth which could consistently claim to be the land of the free.”

Upon Bright’s return to South Pass, two local residents, paid a visit to William and his wife Julie, these were Esther Morris and her son Robert.

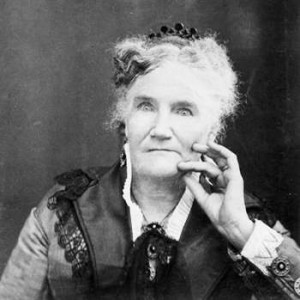

Born Esther Hobart McQuigg on August 8, 1814, near Spencer, New York, she was the eighth of eleven children. Orphaned at age eleven, Esther worked as an apprentice to a seamstress before marrying Artemus Slack in 1841. Her first son Edward Archibald Slack (who went by Archibald) was born one year later. Artemus’ job as a civil engineer required his travel throughout the Upper Midwest, where he was accidentally killed in Illinois.

Esther took her son and moved to Peru, Illinois, to claim her late husband’s property, but faced the difficulties so many women of the time did in claiming property. Therefore, she married John Morris, a Polish immigrant and prosperous merchant. Esther gave birth to three more sons, John (who died in infancy) and twins, Robert and Edward, in 1851.

John and Archibald moved to South Pass in the spring of 1868 to mine gold, but like many others who rushed to the Sweetwater mines they were initially discouraged to find that little surface gold existed. They eventually purchased mining and business property including the Mountain Jack, Grand Turk, Golden State and Nellie Morgan lodes, and even though he had lived in the town less than six months Archibald was appointed South Pass City’s constable. This reflected upon his energetic and congenial character and the significant turnover in South Pass’ population and appointed officers during the first year of the boom.

Esther and the twins followed to South Pass in July, 1869, and all the men soon found jobs. John eventually purchased a saloon in 1873, although he continued to mine and speculate. Archibald became the clerk for the territory’s third judicial district for eighteen months in addition to buying several lots in the settlement he was an agent for the John W. Anthony sawmill company. Robert also served as an agent for the lumber company and was soon appointed deputy district clerk, while Edward’s clerking was confined to a store.

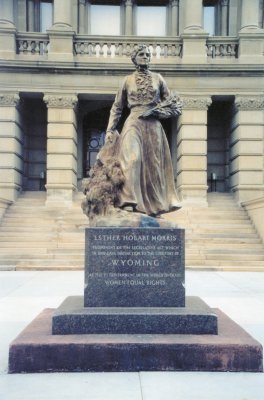

However, it was Esther whose name would go down in the annals of Wyoming history and become synonymous with women’s suffrage in Wyoming. Always a stringent supporter of women’s suffrage movement she took up the cause after moving to South Pass.

In 1869, James Stillman, Justice of the Peace in South Pass City resigned his position. While there are numerous speculations as to why Stillman resigned the most logical is his distaste for Republicans and Governor Campbell and the Governor’s questions involving the appointment of some officers in the county. Stillman, opposed to the Governor’s interference in the county, resigned.

With the encouragement of a few local residents and the support of District Court Judge John W. Kingman, Esther Morris submitted her application to become the Justice of the Peace for South Pass City. County commissioners approved her application on February 12, 1870, making her the first woman judge in the United States. This action created immediate controversy. Stillman refused to give his docket and remaining records to the board in protest at being replaced by a woman, and Commissioner John Swingle claimed he opposed Esther’s application rather than approved it as recorded in the minutes. In any case, her appointment became a split decision.

With the encouragement of a few local residents and the support of District Court Judge John W. Kingman, Esther Morris submitted her application to become the Justice of the Peace for South Pass City. County commissioners approved her application on February 12, 1870, making her the first woman judge in the United States. This action created immediate controversy. Stillman refused to give his docket and remaining records to the board in protest at being replaced by a woman, and Commissioner John Swingle claimed he opposed Esther’s application rather than approved it as recorded in the minutes. In any case, her appointment became a split decision.

Her son Archibald and postmaster G.W.B. Dixson underwrote her five hundred dollar bond, the board sent the nomination to Acting Governor Edward Lee, who approved it two days later, and Esther’s appointment was official.

Esther, knowing the entire country and particularly the citizens of South Pass would be closely watching her actions and decisions probably hoped for a few routine cases to begin her tenure as justice. This was not to be, and she received the most difficult challenge she faced in her job, the prosecution of James Stillman for not relinquishing the docket.

February 17, 1870, citizens packed South Pass City’s rented courtroom to see the female judge in action. Arrested just minutes before his trial, Stillman was escorted to the log building. Upon a motion by Stillman’s lawyer, Mrs. Morris agreed to postpone the proceedings for the remainder of the day to allow the defense time to prepare their case. When court reconvened, the room was again packed, and businesses in South Pass closed for the day. The defense attorney argued Stillman’s arrest was not completed correctly. Esther agreed and dismissed the case, but immediately issued a new warrant to begin proceedings again. Finally, the defense argued as Stillman’s successor, she had an interest in the docket’s return. She agreed and dismissed the case.

Since Stillman retained the docket, Morris purchased a new book to record the twenty-seven cases she tried during the next eight months. Most complaints consisted of disagreements over debts, although she presided over ten assault cases, three with the intent to kill. Often those who practiced law in her courtroom presented the most trouble to routine cases, as men like Attorney Benjamin Sheeks, an ardent opponent of woman suffrage, tried her patience and sought to make trouble in her courtroom.

With national attention focused on Morris and her work, rumors and myths inevitably crawled out of the minds of newspaper men. One story asserted Esther tried her husband for drunkenness and had him tossed in jail. Denying it she replied, “A man is not alowed [sic] to be the judge of wife much less a woman of her husband. It would not be a legal proseding [sic].” Common sense more than knowledge of the law, explains the success of Esther’s tenure.

Despite their initial misgivings about a female justice, Esther managed to recruit many supporters among the citizens of South Pass, and many became advocates of women’s suffrage. By the time her term ended in October, the territory was organized and residents would now vote for their town’s justice of the peace. Esther declined to seek election.

Her son, Robert, explained his mother’s decision by noting she received “much glory” from holding the job and demonstrated a woman could perform well in elected offices. In summary, she had accomplished her goals. Also, the stress generated by the national publicity and initial opposition affected her. She wrote a cousin, “…the post was given to me but the frightful fact is that no man nor woman can hold it all.” Her husband, who opposed women’s suffrage and her job as justice of the peace was also a source of anxiety. And finally, if she decided to seek election her opponent would be none other than James Stillman. Not wanting to cause further discord in her town, already suffering from the mining bust she did not seek election. Stillman won the election, and Morris gave him her docket.

Though her time in office was over, Esther continued to champion women’s suffrage as it faced repeal many times. The general opposition to women’s suffrage included both sexes, for most of the women refused to become involved in politics, voting or otherwise. As a result of this attitude, Esther Morris, a Republican, was the only woman to attend South Pass City’s Democratic meeting in September 1870.

After the very harsh winter of 1871-1872, in which the snow was still twelve feet deep in June, and because of her deteriorating marriage, Esther left South Pass City to live with her son Archibald in Laramie. After refusing a nomination for territorial representative on woman’s party ticket in 1873, Esther moved to Albany, New York, and then Springfield, Illinois, where she spent her winters. In the early 1880s she moved back to Wyoming to live with her son, Robert in Cheyenne.

In 1895, Esther was elected as a state delegate to a national woman suffrage convention in Cleveland. Esther Hobart Morris died in Cheyenne in 1902. Morris’ example inspired men and women to keep up the fight for women’s suffrage and repeal after repeal was defeated in the Wyoming territorial and state governments. She would be the first woman to hold office in the nation and her example would eventually lead to another first in Wyoming and the nation when Nellie Taylo Ross, who moved to Wyoming the year Esther died, would become the first woman governor in the United States, and one of the first women in history to hold a cabinet post when Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected.

It is Esther’s son Robert who is credited with Wyoming’s motto as the “Equality State.”

It is Esther’s son Robert who is credited with Wyoming’s motto as the “Equality State.”

WHOOEEE I’d say that’s one tough Wyoming woman, but then again Wyoming only makes ‘em tough!! Cookie has the supplies loaded (after stoppin’ all the dang time to jaw with Mrs. Morris). .. “Yeah ya did, ya old coot, ‘bout the fourth cup of Arbuckle’s and I was leavin’ yer hide behind…Don’t ya glare at me…”

Sorry ‘bout that, but now that Cookie’s backside in on the buckboard and I’ve cinched up the saddle and stepped into leather we’re on our way again, so join us for more Wyoming history and a bit of fun next Monday!

See ya on the trail!

SOURCES:

“Reform is Where You Find It: The Roots of Woman Suffrage in Wyoming” by Michael A. Massie. www.wyoarchives.state.wy.us/Research/pdf/WomanSuffrage.pdf

Awesome history! Thanks for posting about this incredible woman. Judge Judy can’t hold a candle to her for grit. 😉

LOL, Meg! No Esther Morris could definitely teach Judy what tough really means! Morris has always been one of my favorite people from history, but I never knew what a role her son Robert played in the women’s suffrage movement in Wyoming, so that was a fun piece of history to learn. Thanks so much for stopping by the campfire, and I’m so glad you found the post interesting. 🙂

–Kirsten Lynn

That was a great story and a great lady.

Thanks, Ella! I’m glad you found Esther’s story interesting.

–Kirsten Lynn

Fabulous post, Kirsten. What an amazing woman.

Thanks so much, Ally! Esther Morris’ life both before, during and after her tenure as justice of the peace is extremely interesting. I found it especially interesting that her husband was in such opposition to women’s suffrage and her position as justice of the peace, and yet her sons all threw their full support behind her. She must have been a wise mother, as well. 🙂

–Kirsten Lynn

Once again, an informative Wyoming post. I enjoyed it very much.

Thanks, Alethea! I’m glad you could stop by the campfire and you enjoyed the post!

–Kirsten Lynn

I love history blogs concerning women who made a difference in our country. Too often these brave ladies are forgotten. Thanks.

Thanks, Sharla Rae, I’m glad you found Esther Morris’ life interesting. I like reading about women who made a difference, as well, they’re such and inspiration.

–Kirsten Lynn