Shoot fire! Can y’all believe we’ve made it to the end of the trail in Big WYO! My backside feels like it’s done become a part of this here buckboard and I haven’t even shot Cookie! So all in all I’d call this here trip a humdinger!

But Cookie and me are bustin’ our britches cause we’re rollin’ into a place near and dear to us at this time ‘cause it’s where my current work in progress takes place, so we feel like we’re comin’ on home! And wouldn’t it just blow yer great aunt’s bloomers up, we get to visit this here place this summer for about the thousandth time but South Pass City never gets old! Why there’s enough shootin’, drinkin’, fightin’, and spittin’ goin’ on here to keep any cowpoke happy. Not that Cookie and me participate in any of the like. ;o)

So let’s roll on in and see what’s all the ruckus is about in South Pass!

Long before the first trappers set foot in the Rockies, or thousands upon thousands of emigrants set across the country in search of gold, or land, or escape from a war torn North and South, humans used a natural gateway through the Rocky Mountains. This pass is known today as South Pass, and has been used for trade and travel for thousands of years. Paleolithic hunters camped in the area for at least ten thousand years, and the entire area is rich in Plains Archaic and Late Prehistoric artifacts.

The earliest descriptions of this elevated plain depict a paradise for bison on both sides of the pass, and the large herds represented a great prize for hunters whose lives depended upon the shaggy beasts. The most successful of these people of the buffalo were the Absarokas, better known as the Crow, who battled for control of this rich country with their ancient enemies the Blackfeet and Shoshones. As white traders introduced firearms and horses, however, the balance of power shifted, and by the time the bison disappeared from the Green River Valley, the Shoshones controlled all the country west of South Pass.

Later travelers on the Oregon-California Trail told of meeting Crow, Arapahoes, Bannocks, Cheyennes, Nez Perce, Lakotas, and Utes in or near South Pass. During the golden age of the overland trails, the Shoshones dominated the region and used the pass most heavily.

In 1812, one of the American Indian tribes who used this pass mentioned the natural corridor to an American fur trader, Robert Stuart. Though French and American fur traders wandered the northern Rockies before the return of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, and Indian nations used the corridor for centuries, no one of European extraction appears to have so much as heard a rumor of the pass’ existence before August 1812. The history of this great pass and that of the United States was set on a course of change from that moment.

Stuart’s “discovery” of South Pass in 1812, was recognized by some as the momentous breakthrough it was. The “Missouri Gazette” quickly announced the news and published a full description of the Astorian’s harrowing journey. A brief report printed on 8 May 1813 predicted this showed “the world that a journey to the Western Sea will not be considered of much greater importance than a trip to New York.” But, remarkably, South Pass was quickly forgotten. Some speculated John Jacob Astor suppressed the news of South Pass, hoping to keep it a trade secret. Stuart’s journal remained unpublished for more than a century after his historic journey. More likely, it was the fact the news arrived in the middle of the War of 1812. This war drove Americans from the upper Missouri River and halted the nation’s western trade and exploration activities for ten years.

Stuart’s “discovery” of South Pass in 1812, was recognized by some as the momentous breakthrough it was. The “Missouri Gazette” quickly announced the news and published a full description of the Astorian’s harrowing journey. A brief report printed on 8 May 1813 predicted this showed “the world that a journey to the Western Sea will not be considered of much greater importance than a trip to New York.” But, remarkably, South Pass was quickly forgotten. Some speculated John Jacob Astor suppressed the news of South Pass, hoping to keep it a trade secret. Stuart’s journal remained unpublished for more than a century after his historic journey. More likely, it was the fact the news arrived in the middle of the War of 1812. This war drove Americans from the upper Missouri River and halted the nation’s western trade and exploration activities for ten years.

In 1822, with the reawakening of the American fur trade an ambitious Missouri entrepreneur, William Ashley, advertised he and his partner, Major Andrew Henry, were looking for one hundred “Enterprising Young Men” willing to spend as many as three years risking their lives in the fur trade. Among those who answered his call were Jedediah Smith, the four Sublette brothers, Thomas Fitzpatrick, John H. Weber, David Jackson, Daniel T. Potts, Louis Vasquez, and Mike Fink. [Any of these names ringin’ a bell folks?]

The first two years were marked with repeated failures as Indian tribes employed all they  had to keep the trappers out of their country. Finally, William Sublette, Jedediah Smith, and Thomas Fitzpatrick led a party of some sixteen men up the White River hoping to reach the beaver rich country along the Spanish River (today’s Green River). The Great Plains, Badlands, and Rocky Mountains stood between the fur traders and their goal. On top of all that, it was already late in the year, October, when they set out on their trek. After an arduous trek “crossing several steep and high ridges that “in any other country would be called mountains,” the exhausted men sought shelter at the Crows’ main camp high on the Wind River, probably near today’s Dubois, Wyoming, but perhaps farther downstream at Riverton.

had to keep the trappers out of their country. Finally, William Sublette, Jedediah Smith, and Thomas Fitzpatrick led a party of some sixteen men up the White River hoping to reach the beaver rich country along the Spanish River (today’s Green River). The Great Plains, Badlands, and Rocky Mountains stood between the fur traders and their goal. On top of all that, it was already late in the year, October, when they set out on their trek. After an arduous trek “crossing several steep and high ridges that “in any other country would be called mountains,” the exhausted men sought shelter at the Crows’ main camp high on the Wind River, probably near today’s Dubois, Wyoming, but perhaps farther downstream at Riverton.

During their ten week stay, a Crow told Thomas Fitzpatrick about a pass that existed in the Wind River Mountains, through which he could easily take his whole band “upon the streams on the other side.” In late February eleven men left the safety of the Crow village to find this passage.

Bitter cold and Wyoming wind made the search for the passage a grueling journey. After several days of travel, the party moved over a low ridge, likely the Beaver Divide, and struck the Sweetwater River where they camped. One of the men, James Clyman, recorded that after holding up for three weeks near what became Independence Rock the trappers struck out in a Southwesterly direction. After another week of travel and another bitter night in sagebrush fighting high winds, Clyman said the next day the trappers realized they “had crossed the man ridge” of the Rocky Mountains. This simple announcement marked the first east-to-west crossing of South Pass.

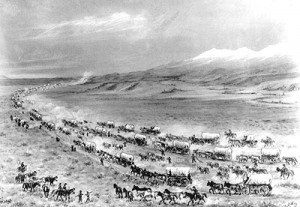

It was the first crossing, but it opened the door for thousands of crossings to come. In the wake of the Rocky Mountain fur trade, the knowledge that wagons could cross the continent to Oregon, and that women (Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding) had successfully completed the journey altered the way American people thought about the Far West. While there was not an immediate flood of emigrants to the West, by 1843, South Pass was “already traversed by several different roads,” according to John C. Fremont. The number of roads across the open plain increased with the intense traffic that arrived with the California gold rush as travelers sought out campsites that had not been stripped of grass. Jim Bridger told one Forty-niner, “he could make fifty roads through South Pass.” By 1848, about 18, 847 Americans had crossed South Pass on their way to new homes in the West.

It was the first crossing, but it opened the door for thousands of crossings to come. In the wake of the Rocky Mountain fur trade, the knowledge that wagons could cross the continent to Oregon, and that women (Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding) had successfully completed the journey altered the way American people thought about the Far West. While there was not an immediate flood of emigrants to the West, by 1843, South Pass was “already traversed by several different roads,” according to John C. Fremont. The number of roads across the open plain increased with the intense traffic that arrived with the California gold rush as travelers sought out campsites that had not been stripped of grass. Jim Bridger told one Forty-niner, “he could make fifty roads through South Pass.” By 1848, about 18, 847 Americans had crossed South Pass on their way to new homes in the West.

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in California, would transform South Pass and the nation, as the steady flow over the pass turned to a river. By 1860, trail historian John Unruh, calculated almost 300,000 men, women, and children had crossed South Pass.

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in California, would transform South Pass and the nation, as the steady flow over the pass turned to a river. By 1860, trail historian John Unruh, calculated almost 300,000 men, women, and children had crossed South Pass.

California wasn’t the only place experiencing a rush due to the finding of gold. In 1864, officers and men from the Eleventh Ohio Volunteers, sent west to guard the telegraph during the Civil War, became convinced that there was enough gold on the upper Sweetwater to make them rich. By the end of the Civil War the West was overrun with experienced prospectors. Fort Bridger commandant Major Noyes Baldwin and Captain John F. Skelton grubstaked John A. James and D.C. Moreland to spend six months surveying the mineral prospects of South Pass. Along with miners they found already operating in the area, the men organized the region’s first mining district, the Lincoln, on November 11, 1864 on a tributary of Beaver Creek. The men found all types of gold, ranging from very fine quality flour gold to course gold. Moreland, James, and their associates began mining on the Willow Creek, where South Pass City eventually grew. This mine was abandoned when the miners were run off by Indians, but others returned to the area to take up where these men left off.

California wasn’t the only place experiencing a rush due to the finding of gold. In 1864, officers and men from the Eleventh Ohio Volunteers, sent west to guard the telegraph during the Civil War, became convinced that there was enough gold on the upper Sweetwater to make them rich. By the end of the Civil War the West was overrun with experienced prospectors. Fort Bridger commandant Major Noyes Baldwin and Captain John F. Skelton grubstaked John A. James and D.C. Moreland to spend six months surveying the mineral prospects of South Pass. Along with miners they found already operating in the area, the men organized the region’s first mining district, the Lincoln, on November 11, 1864 on a tributary of Beaver Creek. The men found all types of gold, ranging from very fine quality flour gold to course gold. Moreland, James, and their associates began mining on the Willow Creek, where South Pass City eventually grew. This mine was abandoned when the miners were run off by Indians, but others returned to the area to take up where these men left off.

In July 1867, the “Chicago Times” reported, “Salt Lake papers of July 1, received here, give  accounts of rich gold discoveries in the mines are located in Green river [sic] country…” Reports stated the road to the Green River was crowded with citizens from Salt Lake, and the new gold mines “set the people wild in this locality.” Papers and reports from the area and the East kept up the steady drumbeat and Wyoming’s gold rush was on.

accounts of rich gold discoveries in the mines are located in Green river [sic] country…” Reports stated the road to the Green River was crowded with citizens from Salt Lake, and the new gold mines “set the people wild in this locality.” Papers and reports from the area and the East kept up the steady drumbeat and Wyoming’s gold rush was on.

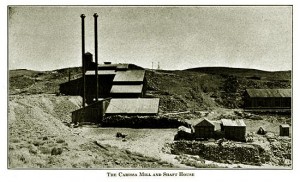

What was discovered by grizzled mountain man, Lewis Robinson, in June 1867, was the Carriso ledge, which soon became the Carissa Mine. By late July there were already several other prospects that looked as good if not better, including the Morning Star, Melrose, Copperopolis, and Last Chance. Half a mile below the Carissa Mine, prospectors soon began building South Pass City. By early November, the settlement boasted fifty houses and several stamping mills. At year’s end, the Dakota Territorial Legislature made the boomtown the seat of Carter County, after the formation of Wyoming Territory, the county was renamed Sweetwater County.

In an entreaty for a post office, it was reported that by March of 1868, the population of South pass was 1,000 and it was anticipated that within one or two months, the town would have 3,000. A postal agent from Salt Lake City estimated that within a few months the City would attain a population of 10,000. Regardless, there was a need for a post office. It cost $1.00 to send a letter by private express. The road from Sweetwater to South Pass City passed over 75 miles through land “destitute of water. George W.B. Dixson was named as postmaster. However he absconded with some of the government’s money, allegedly to the newly found Cape Colony where he remained until his wife died. He ultimately returned to the United States and died in Chicago.

Despite the postmaster’s less than honorable behavior, South Pass City retained a post office along with a newspaper, five hotels, and some fifteen saloons including: the “49’er,” “Keg,” “Magnolia,” “Elephant,” and the “Occidental.” By 1868, the town had stage service south to Bryan on the Union Pacific. By 1869, Iliff & Co. had opened the Exchange Bank and a toll road to Atlantic City 2 and half miles away opened.

Despite the postmaster’s less than honorable behavior, South Pass City retained a post office along with a newspaper, five hotels, and some fifteen saloons including: the “49’er,” “Keg,” “Magnolia,” “Elephant,” and the “Occidental.” By 1868, the town had stage service south to Bryan on the Union Pacific. By 1869, Iliff & Co. had opened the Exchange Bank and a toll road to Atlantic City 2 and half miles away opened.

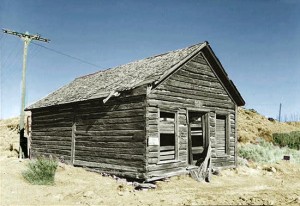

If the growth of South Pass City was rapid, its decline was equally as fast. By 1870 the bank closed and in 1871 there was a disastrous fire. The Carissa Mine remained the chief mine at South Pass City, and by 1868 some $15,000.00 of gold had been mined, but by 1873 the mine was idled, the gold rush over. Governor J.W. Hoyt reported in 1878 that “South Pass is a scene of vacant dwellings, saloons, shops, and abandoned gulches.” For some who came and left, the big strike and fortune was just over the next hill, and when the government opened the Black Hills they followed the scent of gold.

If the growth of South Pass City was rapid, its decline was equally as fast. By 1870 the bank closed and in 1871 there was a disastrous fire. The Carissa Mine remained the chief mine at South Pass City, and by 1868 some $15,000.00 of gold had been mined, but by 1873 the mine was idled, the gold rush over. Governor J.W. Hoyt reported in 1878 that “South Pass is a scene of vacant dwellings, saloons, shops, and abandoned gulches.” For some who came and left, the big strike and fortune was just over the next hill, and when the government opened the Black Hills they followed the scent of gold.

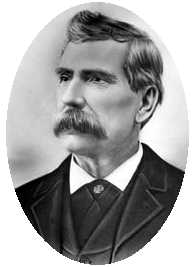

Despite its short boom, South Pass City, is noted not only for the gold mines, and as a  stop on the Oregon Trail, but as the home of women’s suffrage. In 1869, William H. Bright, South Pass mine and saloon owner, was elected to the First Territorial Assembly. He introduced a bill providing for woman’s suffrage which was passed by the legislature and approved by Governor John A. Campbell. There are various versions regarding Bright’s motivation for introducing the bill. One is that Bright was persuaded to do so by a promise made to Esther Hobart Morris, later the first woman justice of the peace in the United States. Another is that Bright was influenced by his wife, Julia, to introduce the act. Another theory is the Democrat controlled legislature thought women would vote Democrat to offset the Black community that tended to vote Republican. However, if this was the case it backfired, since this was in the days before the “Australian” or secret ballot, and it was soon discovered women tended to vote Republican. In any case, two years later the Democratically controlled legislature attempted to repeal woman’s suffrage, but the act to repeal was vetoed by the Republican Governor, and enough Republicans had been elected (thanks to women) to sustain the veto.

stop on the Oregon Trail, but as the home of women’s suffrage. In 1869, William H. Bright, South Pass mine and saloon owner, was elected to the First Territorial Assembly. He introduced a bill providing for woman’s suffrage which was passed by the legislature and approved by Governor John A. Campbell. There are various versions regarding Bright’s motivation for introducing the bill. One is that Bright was persuaded to do so by a promise made to Esther Hobart Morris, later the first woman justice of the peace in the United States. Another is that Bright was influenced by his wife, Julia, to introduce the act. Another theory is the Democrat controlled legislature thought women would vote Democrat to offset the Black community that tended to vote Republican. However, if this was the case it backfired, since this was in the days before the “Australian” or secret ballot, and it was soon discovered women tended to vote Republican. In any case, two years later the Democratically controlled legislature attempted to repeal woman’s suffrage, but the act to repeal was vetoed by the Republican Governor, and enough Republicans had been elected (thanks to women) to sustain the veto.

The mine that started it all, the Carissa, was reopened in 1901 and the size increased, but was closed again in 1906. In 1946, the mine was again reopened and quickly closed. The three towns that boomed in Wyoming’s short gold rush, South Pass City, Atlantic City, and Miner’s Delight, have faded to ghost towns.

The mine that started it all, the Carissa, was reopened in 1901 and the size increased, but was closed again in 1906. In 1946, the mine was again reopened and quickly closed. The three towns that boomed in Wyoming’s short gold rush, South Pass City, Atlantic City, and Miner’s Delight, have faded to ghost towns.

But turn yer wagons into South Pass and y’all will still receive a big WYO welcome. You can see the home of Mrs. Esther Morris (a topic for a blog in the very near future), the Carissa Saloon, The Sherlock Store and the Sherlock Motel (originally the Idaho House), the Exchange Bank and other remains of a city that saw more history in its short boom than some see in a hundred years, and a pass that has served as a gateway for thousands of years.

Cookie and me are headed on over to Sherlock’s to gear up for a new adventure, and maybe I’ll talk the ol’ coot into a game of billiards and a cold one over at the saloon.

Cookie and me are headed on over to Sherlock’s to gear up for a new adventure, and maybe I’ll talk the ol’ coot into a game of billiards and a cold one over at the saloon.

Well folks, just a few miles from South Pass is what they call the Parting of the Ways where those early pioneers chose one path to California or the other to Oregon. And Cookie and me, well we don’t veer left or right, but stay right here in this part of the West we’re just as happy as pigs in mud to call home. So, we’ll let y’all choose the path that fits yer fancy as we say so long to the trails!!

SOURCES:

Another wonderful post. I don’t know why I never learned much in school about the western United States. I think we covered Lewis & Clark and the Civil War and moved on to the Industrial Revolution without studying much about the west.

Thanks so much, Ally! The more I hear people say about what they didn’t learn in school, the more I realize how fortunate I was. I had fabulous history teachers, but most of all I had a dad who took us on long road trips (and still does when I visit) and knows his Wyoming history. I’m so glad I could bring some of this history to you. 🙂 Hope you’ll stick with Cookie and me as we forge ahead! 🙂

–Kirsten Lynn

Wonderful post and pictures! We took a modern-day wagon train trip around the Tetons not long ago and it was beyond words. Loved every second of it. Okay, okay, we had rubber tires and padded seats but…surreal anyway LOL..

Wonderful to see you out on the trail, Tanya! Thanks for the kind words. I’ve always wanted to go on a wagon train, and one around the Tetons would be amazing! All the better if there’s padded seats, I say. 😉

–Kirsten Lynn